香港自2020年初出現首宗2019冠狀病毒確診以來,三年間疫情反覆,演出場地須因應防疫措施調整入場人數,甚或閉館。香港表演藝術工作者在這艱難時期,仍然孜孜不倦投入創意與能量,尋求數碼展演的可能性。

本計劃由國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)策劃,目的在於整理、紀錄和研究疫情下的香港表演藝術發展,建構首個以網上作品為核心的資料庫,作為研究和交流的基礎。作品收錄原則如下:

• 於2020年1月1日至2021年12月31日期間透過網上平台首次發表;

• 由香港職業、業餘藝團、藝文組織主辦或製作;

• 為全新製作,或因應網上發表方式重新在創作上進行處理的舊作;

本計劃亦透過舉辦「劇場/不/停/封:『演上線』計劃專題講座系列」,邀約本地和海外的網上展演實踐者與藝評人,分享美學探索經驗,探討「後疫情時代」劇場與表演藝術的本質;其中系列(一)由捷克藝術與劇場研究中心協辦。

計劃同時委約三位藝評人(許樂欣、鄧正健、雷浩文)進行「網上展演」的研究,並就研究成果發表專題文章。此外,本網站亦收集了與網上展演發展有關的藝評文章和講座,以延伸資料的方式包含在本網站內。

本網站的資料來源包括但不限於藝團修訂、演出網站、演出場刊或社交媒體平台,圖像版權屬主辦或製作單位所有。資料來源如有更新,會以該來源為準。如有疑問,歡迎讀者透過電郵(iatc@iatc.com.hk)向本會提出。

【免責聲明】

國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)(下稱本會)將盡力確保本網站的資料準確性,但不承諾本網站或本網站的任何資料或內容將無任何錯誤或遺漏,亦不承諾任何瑕疵將被修正。本會不會就任何錯誤、遺漏、錯誤陳述或失實陳述(不論明示或隱含的)承擔任何責任。本網站內一切內容可能會隨時變更,而不另行通知。

本網站所載的內容並不代表本會之立場。

本會不會對使用或任何人士使用本網站而引致任何損害(包括但不限於電腦病毒、系統固障、資料損失)承擔任何賠償。本網站可能會連結至其他網站,但這些網站並不是由本會所控制。本會不會對這些網站所顯示的內容作出任何保證或承擔任何責任。閣下如瀏覽這些網站,將要自己承擔後果。

本會保留隨時更新本免責聲明的權利,任何更改於本網站發佈時,立即生效。請在每次瀏覽本網站時,務必查看此免責聲明。如 閣下繼續使用本網站,即代表同意接受更改後的免責聲明約束。

香港藝術發展局全力支持藝術表達自由,本計劃內容並不反映本局意見。

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Hong Kong in early 2020, the pandemic has remained persistent over the past three years. Performance venues have had to cut back on seating capacity or even close their doors in response to infection prevention measures. In these difficult times, Hong Kong performing arts practitioners are still tirelessly injecting their creativity and vitality into the local scene, seeking new possibilities in the realm of digital performance.

This project was initiated by the International Association of Theatre Critics (Hong Kong) to chart and examine the development of performing arts in Hong Kong amidst the pandemic, and to construct the first archive with online works as its core to serve as the foundation for research and exchange. To be eligible for inclusion into the archive, a work must be:

• First published via an online platform between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021;

• Organised or produced by a Hong Kong-based professional or amateur arts group, or cultural organisation; and

• A brand-new production, or an old work that has been revamped in the creative aspect for the purpose of online presentation.

The initiative invites local and overseas online performance practitioners and art critics to share their experience in aesthetic exploration and enquire the nature of theatre and performing arts in the “post-pandemic era” through The Show Must Go On(line): Online Performance Archive Thematic Talk Series. The inaugural series was held in collaboration with the Arts and Theatre Institute (ATI) of the Czech Republic.

Three art critics (Sally Hui, Tang Ching Kin, and Felix Loi) have also been commissioned to conduct research on “online performance” and publish feature articles on their findings. In addition, art criticism articles and lectures concerning the development of online performance will also be gathered and made available on this website as extension materials.

Sources of the information provided on this website include, but are not limited to, editorials by arts groups, performance websites, house programmes, and social media platforms. The image copyrights belong to the relevant organisers or production units. Should any updates be made, the information at the source shall prevail. Readers are welcome to send any questions they may have to the Association via e-mail (iatc@iatc.com.hk).

【Disclaimer】

Whilst the International Association of Theatre Critics (Hong Kong) [IATC(HK)] endeavours to ensure the accuracy of the information on this website, IATC(HK) does not guarantee that the site or any content is error-free, or that any defects will be corrected. IATC(HK) does not have or accept any liability, obligation or responsibility for any errors in, omissions from, or misstatements or misrepresentations concerning, whether express or implied, any such content. The site and its content are delivered on an "as-is" and "as-available" basis, and are subject to change without notice.

The content on this site does not represent the stance of IATC(HK).

IATC(HK) shall not be liable for any damages (including, but not limited to, computer viruses, system problems, or data loss) whatsoever arising from the use of, or in connection with the use of, this website by any party. There may be links in this site which will direct you to other websites not controlled by IATC(HK). IATC(HK) will bear no responsibility and no guarantee for whatsoever content displayed on such sites. Following hyperlinks to other websites is at your own risk.

IATC(HK) reserves the right to update the Disclaimer at any time with or without prior notice. All changes are effective immediately upon posting to the website. You are hereby invited to check the Disclaimer each time you visit the website. Your continued use of the website thereafter constitutes your agreement to all such changes.

The Hong Kong Arts Development Council fully supports the freedom of artistic expression. The views and opinions expressed in this project do not represent the stance of the Council.

讓我們回憶一下新冠肺炎剛爆發時的情況:起初,人們以為疫症只是在局部地區發生,也沒料到會蔓延很久。一些防疫、隔離措施開始在各地實行,但整體上不算嚴厲,或者應該說:即使當局不說,但人們普遍都在想:疫症很快就過去,我們盡量不要讓防疫影響正常生活。於是「正常生活」成了「全球疫症」的反義詞: 當疫症開始以無法想像的速度在全球所有地區爆發時,我們也彷彿從疫症蔓延的軌跡上,看到甚麼是所謂「全球化」。

疫症就像當代全球人類互動交流網絡的顯影劑,我們忽然發現,即使在互聯網時代,我們常常口口聲聲說,人與人之間的實體距離因虛擬世界而消失,但現實卻是,網絡從來沒有取代過實體交流。不論在宏觀經濟和文化角度看,或在微觀的人際社交層面上看,莫不如是。而所謂「正常生活」,恰恰就是這種人與人之間的「實體接觸」。

死亡、隔離和封城持續在世界各地出現,令人不禁想起諸如卡繆(Albert Camus)的《瘟疫》之類的文學想像,或中世紀的「黑死病」一類文明衰敗的徵兆。不過,想像歸想像,新冠肺炎實際上沒令我們對「世界末日」有過多揣測,死亡漸漸變成一個數字,全球治理主流也很快以「恢復正常生活」為目標。

問題是,對於「正常生活」的定義,已在兩年多的疫症之中被完全改寫。在隔離期間,人們失去了實體交流的機會,但交流的慾望不僅沒有消失,反而具體轉化成兩種情緒。一是希望以「保持交流」作為對「正常生活」的新定義,哪怕只是網上交流,於是網上視像軟件突然成為生活必需品,「在家工作」(work from home, WFH)也成了新常態;二是完全反過來,對「網上交流」產生巨大厭惡,並重提過去對網絡社交種種負面而帶有「科技恐懼」(technophobia)的言論,並以此作為必須「恢復(疫症前的)正常生活」的理據。

因為有效疫苗的出現,一些政府可以「與病毒共存」作為恢復正常生活的條件,繼而加快恢復正常社會運作的步伐;另一些政府則堅持以「清零」為條件,因而延長了恢復時間。可是,不論是何種政策,其實都無法迴避一個現實:當經歷過隔離、完全放棄實體交流而改用網上交流的生活之後,人們就不能再假裝:我們不需要——或至少不用依賴——網絡交流。換一個說法,疫症中的隔離生活逼使我們必須思考:「正常生活」還有甚麼部份必須維持「實體經驗」?而可以被置換成網上的「正常生活」,跟過去又有甚麼不同?

就是在這種處境下,當代劇場被拋入了一個史無前例的轉折中。疫症踏入第三年,香港劇場仍然沒法「完全」恢復疫症前的「正常」。這個問題包含了起碼三個意思:

一是關於劇團營運和製作上的「正常」。由於疫症和政府防疫政策反覆,表演場館不時突如其來關閉,或因應防疫措施而減少觀眾席座位和場次。二〇二〇年一月二十九日,康樂及文化事務署首次宣布關閉所有表演場地。在兩年多裡,因應疫情反覆,場館數度關閉又重開,同時亦不時更改觀眾席數量、表演者和觀眾的防疫要求等,對劇團來說,自是無法以「正常」方式去規劃製作。他們一方面承受因無法演出、減少場次及觀眾人數而造成的成本風險,另一方面也為減低相應壓力而準備後備方案,如改以網上直播或錄播演出等。

二是關於觀眾觀劇的「正常」。疫症中的隔離生活令觀眾不再視「網上觀劇」為新鮮的事。網絡生活在疫症中變得舉足輕重,連帶過去我們常認為無法以網絡取代的活動,都可以在網絡上完成。「在家工作」自是鮮明一例,其他諸如網課、網上講座、網上博物館甚至是網上拜年,都是隨處可見。或者說,事到如今,當我們打算籌劃一項活動時,「實體」跟「網上」都會是選項,因為疫情,選擇網上進行亦變得更理所當然。劇場觀眾也對劇團作網上演出完全理解,亦漸漸習慣了這種觀劇體驗。

三是關於劇場本質的「正常」狀態。雖然說,我們好像已習慣了網絡生活,也愈來愈視「實體」跟「網上」為兩個不分主次、沒分「正常」或「後備」 的選項,但當「劇場在網上」被正常化,我們(包括創作者、觀眾和評論人)也不得不重新思考關於一個劇場本質的問題:如果不在現場,劇場還是劇場嗎?或問:如果不在現場,劇場可以是怎樣的劇場呢?全球疫症不只根本上改變了劇場創作的模式,也啟發了我們對當代劇場的想像。疫症期間,香港劇場製作大幅減少,但關於當代劇場美學的論述卻意外地蓬勃。

毫無疑問的是,劇場(被逼)網上化大大刺激了創作者、觀眾和評論人的思維。創作者必須從實務上考量,將一個演出放在網上進行,對其美學和製作條件會產生甚麼影響,又如何改變他們的創作方式;觀眾需要學習適應這種劇場形式的結構轉型,以從獲得跟過去既相似、又不同的觀劇經䌞。這些觀眾經驗,可能是更自主,也可能是更受操控的;而評論人則在評論個別作品的優劣之上,必須進一步關注:這種劇場變革如何影響作品的呈現、觀眾接收、乃至從理論上改寫當代劇場的形態,以及未來劇場的發展方向。以上問題,都是香港劇場在(後)疫症時代必須審視的問題。

對於劇場網上化,創作者最初主要有以下兩種應對/處理方式:

一是視網上演出為權宜之計,以維持恆常演出。大量本打算作實體演出的作品「被逼」轉戰網上,創作者往往未及對「網上演出」的形式作太多思考,只能以最簡約的方式,把本來在劇場裡的現實演出或最後綵排錄影,然後播放。這些錄播演出,鏡頭調度相對簡單,也未有仔細考慮劇場現實跟鏡頭影像之間的差異,拍攝出來,往往比較沉悶。

二是在網上播放舊作,以維持劇團營運的活躍度。由於表演場地長期處於「重開無期」的狀態,一些較具歷史和規模的劇團會把舊作的錄影作限時播放,這些錄像本來只作紀錄和備案之用,在錄影時根本沒考慮作公開播映,拍攝質素一般較差。

上述兩種形式,在疫症爆發早期例子相當多。可是,不論是創作者、劇團營運者或是觀眾,對這些「作品」一般都不滿意,主因不在作品創作質素,而是「網上」這種呈現形式。先不論播放平台等純技術問題,很多劇團根本不熟悉「網上劇場」這種形式到底是怎樣一回事,而觀眾亦同樣不熟習相應的觀劇經驗。劇場觀眾是需要「訓練」的,意思是說,觀眾透過持續進入劇場觀劇,逐漸熟習劇場的「現場感」。這種「現場感」包括對作品內容和訊息作理性上的認知和判斷,但更重要的,卻是包含了各種感官統合的整體感知,即一種「體驗」或「沉浸」(immersive)。而網上觀劇則是徹底破壞了這種在劇場觀眾身上已累積多年的體驗。很多觀眾都覺得,網上觀劇的經驗不好,在於無法投入,具體則體現於以下幾點:

一是缺乏現場感。網絡和鏡頭成為觀眾跟演出和表演者之間的屏障,觀眾一開始就清楚意識到,自己跟演出並不身處同一物理空間(劇場)之內,過去積累下來的「觀劇經驗」都無法再現;

二是失去儀式感。「進入劇場,關燈,然後演出開始。」這是過去劇場觀眾必須進行的「觀劇儀式」,而網上觀劇則取消了這種儀式。觀眾首先無法「到劇場去」,無法在演前演後跟其他觀眾和創作人交流,這已是「失去儀式感」的第一步。觀眾亦不用在固定時間和地點觀劇,只「安坐家中」就能看劇。他們會一邊上網觀劇,一邊分心地在家中如常生活,如隨意吃東西、跟家人談天、上廁所、或同時做其他事情等等,這都會進一步消除了劇場的儀式感。至此,在感官經驗上,網上觀劇已跟「看電視」或「網上瀏覽」分別不大了;

三是感官被限制。劇場現場性的好處之一,是觀眾有選擇觀看/接收甚麼的自由。很多觀眾都發現,網上劇場限制了他們的視角。由於舞台上/演區裡並不會只發生一件事,不同演區的演員會有不同演出、舞台上的調度也有整體而多元的呈現,可是網上錄播/直播都是由鏡頭所控制,鏡頭在某一劇場時刻可能是全景,也可能是對某演員、甚至是演員的某身體部份作特寫。這或許是導演跟掌鏡的拍攝者的個人選擇,是美學或技術考慮,卻完全限制了網絡另一邊、「安坐家中」的觀眾的觀劇視角選擇。

而對於現場跟網上的形式差異,不少人都注意到兩點:

第一點是關於劇場與電影的界線。傳統認為,劇場與電影的最大分別,在於「調度」(mise-en-scène)。這個詞本就源自劇場,但後來卻廣泛用於電影裡,其意思是指創作者(主要是導演)如何配置作品中的各種元素。事實上,劇場與電影中的元素十分相似,從內容(故事、情節、對白、演員表演等)到形式(場景、燈光、聲音等),俱是差不多的東西。但「調度」卻根本上區別了兩者:劇場調度發生在舞台/劇場的空間內,而電影調度則發生鏡頭畫面裡。這亦引伸至兩者所呈現的時間性差異,即劇場作品是一個現場發生的連續時間體,而電影則由於利用了剪接而產生時間斷裂。

網上劇場正是一種將劇場電影化的形式。香港觀眾比較熟悉的有「英國國家劇院現場」(National Theatre Live,NT Live),即是把劇場演出以電影調度的方式拍攝,再在大銀幕上播放。然而,疫情下香港劇場的網上化作品,一般都未能達到這種影像質素,資源成本是一個問題,製作經驗亦是另一關鍵。不過,更重要的是它要求創作者有這種「劇場電影化」的創作意識,最後能令觀眾產生「觀看電影」、而不是「觀看劇場」的體驗。可是,這些網上播放的香港劇場作品不少缺乏這種創作意識,反而將劇場跟電影的差異進一步放大,干擾著觀眾的觀看經驗。

第二點是關係劇場本質的問題。布魯克(Peter Brook)的名言被一再引述:「我可以選任何一個空的空間,然後稱它為空曠的舞台。如果有一個人在某人注視下經過這個空的空間,就足以構成一個劇場行為。」它成為了人們反思網上劇場的參考點。無疑,「以『空的空間』」定義劇場」這一概念一直籠罩著香港劇場,「空的空間」的關鍵元素有以下幾種:空間、觀看、被觀看、以及現場。而網絡乃是一種「去空間化」及「去現場化」的形式,結果令「空的空間」難於實踐。

同樣地,網上觀劇也破壞了觀眾跟表演者的「觀看」關係。「空的空間」要求觀看者跟被觀看者必須身處同一空間,劇場行為才能夠成立。若按此定義,網上劇場不是「劇場」。而若當創作者跟觀眾一直擁抱這種觀念,所謂網上劇場就永遠只能是一種權宜、暫時的呈現策略,人們最終也是要求「回到劇場去」,劇場才能恢復「空的空間」的那種「正常」。

可是,曠日持久的疫症和隔離措施不只令人失去耐性,亦根本上改變了我們對劇場的認知。可以說,後疫症的劇場正經歷一場當代的範式轉移:「空的空間」不再是那麼本質性,劇場跟電影的差異也變得模糊。但更重要的,是隔離所導致的社會交流網絡化,成為了革新我們想像劇場的催化劑。創作者開始思考一個問題:如果我們必須持續地(而不是權宜、暫時地)進行網上劇場創作,那麼我們應該怎樣處理「網上經驗」跟「劇場經驗」之間的張力呢?

由此,劇場不僅是再一次被帶到舞台之外(第一次可能是布萊希特打破現實主義劇場的第四堵牆), 也是初次被帶進人們的當代網絡經驗之內:我們曾經以為,有一些事情沒法以網上交流代替實體交流,例如劇場體驗,但隨著世紀疫症的蔓延,劇場也開始被劃入「可在網上進行」的活動選項裡。一旦人們接受了這種觀念,一個全新的問題意識就在香港劇場裡滋長,即使疫情緩和、表演場地重開,這種問題意識也不會消失:我們如何把網絡體驗置放於劇場創作之中?

其實,這種問題意識並不新鮮:近年盛行於世界劇場、香港劇場也深受影響的沉浸式劇場(immersive theatre)正是類似的一回事。沉浸式劇場打破傳統劇場框架,強調劇場作品如何築構觀眾的總體經驗,而不是單純的「觀看」。因此,沉浸式劇場大量使用了布萊希特「敘事體劇場」的手段、環境劇場以及偶發藝術等方式,直接將觀眾引進現實生活中的社會經驗之中。當香港劇場創作者試圖處理網絡跟劇場的互動時,首先便得處理個人的網上經驗如何可以作為劇場的形式,例如社交平台、串流技術和網上會議軟件的應用,並延伸至網絡遊戲、視頻和留言版的互動功能等。

舉一些例子。「再構造劇場」的《如何向外星人介紹瘟疫下的香港人感情生活》改編自編導甄拔濤的一個舊作,將原來在實體劇場內進行的「講座劇場」(lecture theatre)改成一個類似網課的形式,同時創作者開放了網上交流軟件上的留言功能,容許觀眾即時留言。創作者的原意十分明確:模擬現實中的網課體驗,也就是嘗試有機地把網絡經驗接合到作品之中,以改寫演出者跟觀眾的劇場關係。劇評人凌志豪指出,觀眾的即時言留言一方面能為劇中敘事帶來「生活感」,但同時又會令其他觀眾「分心」,因而注意到劇本的種種缺點。而作品敘事跟觀眾即時編織出來的「敘事」可能是相輔相成,但亦可能是互相競爭,爭奪觀眾注意力,「把作品引領往另一個方向」。[1]

凌志豪亦比較了另外兩個利用網上會議軟件演出的作品。「微型人種誌劇」《See You Zoom》中的四位演員以軟件分享他們在疫症下的生活,然後再開放給觀眾討論。但凌志豪則認為創作者過度控制觀眾的回應內容方式,如要求觀眾打分,只讓觀眾對特定題目進行回應,使觀眾無法深入表達意見。[2] 至於「一舊飯團」的《兩位thx》,創作人林珍真在四個月的時間內,進行了一百場網上演出,每次邀請一位觀眾在虛擬餐廳上聊天。凌志豪認為作品在設計上只有框架和程序,內容反而是透過演員和觀眾即時交談構成。對他來說,這種在虛擬空間的偶發性相遇,或許是「一種新的劇場類型可能正在萌芽」。[3]

凌志豪的比較點出了劇場網絡化如何改寫演出者跟觀眾的關係。首先,劇場的現場感消失了,但即時性的交流反而比實體劇場更為蓬勃和有效。然而,這種交流是否能產生一種更接近波瓦(Augusto Boal)式、觀眾足以高度介入作品敘事的劇場形態,那就很視乎創作者如何使用「網絡」這種形式。誠如凌志豪的分析,《See You Zoom》對交流的控制過多、《如何向外星人介紹瘟疫下的香港人感情生活》卻太過鬆散無章,《兩位thx》則還需依賴參加的觀眾——作為「素人演員」參與——對交流內容和形式的駕馭能力(這也有一種「演技」),才能產生有效交流。

另外,凌志豪也評論了一個以網絡遊戲為藍本的作品:「天啟創作室」的《我唔係機械人》。作品透過虛擬辦公室軟件模擬網絡遊戲,讓觀眾可自由探索系統內空間和事件。凌志豪認為,這種網絡遊戲形式的網上劇場作品跟互動式電影(Interactive film)的最大分別,是網上劇場要求所有觀眾同時在限時的遊戲空間中出現,這種「共在」的狀況既影響了作品的節奏,其集體性也直接決劇場敘事的走向,而不是如互動式電影那樣,是個人對敘事的選擇。不過,凌志豪亦同時指出,網上空間如可能製造如實體劇場的集體儀式感和群體親密感,也是一個需要繼續探索的問題。[4]

自從互聯網出現以來,網絡體驗以一種既快且慢的速度進入當代人的生活體驗中。 快,是因為網絡技術發展一日千里、普及速度以幾何級數上升;而慢,則是指當代社會一直對互聯網技術抱有戒心,一方面對互聯網所造成的實體交流衰落保持警剔,另一方面也擔心互聯網對人類生活的監控、害怕「數位利維坦」(Digital Leviathan)降臨大地。但一場全球疫症,卻大大加快了當代生活網絡化和虛擬化的速度。人們被逼放棄大部份實體交流,放下對互聯網的恐懼,以維持人與人之間的交流,以免陷入一種存有論上的孤獨。而另一方面,互聯網技術亦重塑了個人的存在方式,以及集體的共同感體驗。

凡此種種,皆成為劇場創作者在進行網上劇場創作時所不能迴避、也必須小心介入的事情。而評論人則對此持續追問箇中成效,以及如何更新我們對當代劇場的認知。劇場編導、同時也是劇評人的甄拔濤樂觀地認為,劇場網絡化可為未來劇場帶來「邁向去中心化的表演模式」,他甚至借用德希達(Jacques Derrida)的解構(Deconstruction)思路,指出劇場網絡化或甚至劇場的衍生媒介(他舉了幾個引入廣播劇和網上短片形式的網上劇場作品為例),是拆解了「劇場傳統定義」這個中心。[5] 甄拔濤沒有清楚說明的是,何為「劇場傳統定義」,大概就是布魯克對「(實體)劇場」的經典定義。這儼然是一種「劇場中心主義」(theatre-centrism),一場疫症,我們似乎找到以網絡予之「去中心化」的前途。

可是,這種樂觀情緒並不能掩蓋人們對劇場未來的焦慮。我們既相信劇場未來的可能性,也深恐劇場會行將毁滅。以下三方面,恰恰能代表人們在疫症下如何想像劇場的未來:

一是現場性。「回到劇場去」的聲音從未中止,大部分劇場創作者仍然堅特「空的空間」的現場體驗。可是,亦有不少人認為,只要我們擴闊對「現場性」的理解,就會發現網上體驗,也可以是一種「(虛擬)現場性」。必須注意的是,「虛擬」不等同「虛假」,它只是另一種(或說是「最當代的」)體驗,尤其在疫症時代中,這種體驗已深入每一個人的生活體驗裡,根本上改變了人類對「生活」的認知。而一種比較調和的說法是,「實體」與「虛擬」並行不悖,它沒有摧毁劇場,只是擴大了劇場的定義。

二是公共性。「劇場公共性」的討論也是一直存在。除了內容上屬「政治劇場」一類作品,「劇場公共性」亦是對劇場形式的訴求,即:劇場的形式或美學如何體現社會或政治的公共性。最直接的理解是,由於劇場的現場性,它可以成為表演者與觀眾互動交流的場域,對公共意見的形成有所幫助。其中尤以波瓦一脈的劇場流派為代表,在香港劇場中則有「一人一故事劇場」(Playback Theatre)的實踐,也是相當流行。

可是,網絡作為當代公共性的展演場域,早已不是新鮮事,尤其在香港多年來的社會運動實踐中,人們早就清楚認識到網絡對公眾輿論塑造、乃至社會運動動員的力量,因此,不少人(像甄拔濤)深信,正如在諸種政治和文化場域裡一樣,網絡可作為一種對劇場作「去中心化」的形式:在網上,觀眾可以透過社交平台、留言版或網上對話軟件,對演出作出比在劇院內更加深入的介入,甚至更簡易地對演出作沉浸式參與。但另一面,我們大可以持完全相反的意見,認為這種網絡的「去中心化」,其實也是一種「原子化」:與觀眾跟觀眾、觀眾跟表演者區隔開來。觀眾「參與」劇場的公共性交流,其實只是一種虛擬性的、幻像式的「參與」,反而更不利於真實的公共對話。我們在凌志豪的分析中可見一斑。

三是文化民主:無可否認,「去中心化」是網絡形式的關鍵概念,尤其在近年興起的區塊鏈技術,令人不禁思考劇場創作的「去體制化」的可能:例如,不需依賴政府資助、不需服膺於市場邏輯,可以借助網絡或其他科技,一方面減低成本,另一方面擺脫上演檔期與場館空間的絕對掣肘,令「劇團創作」跟「觀眾觀看」兩方面都可以更機動、更能體現一種文化上的民主(cultural democracy)。身兼劇評人和劇場監製的肥力,便曾以自身在症疫下的製作經驗力證,劇場網絡化能為劇團和創作人提供各種可能性,讓他們毋需再完全依賴政府和市場資源,可以更機動、更自由地進行創作,進一步實踐不同背景、能力和地域的創作者、以更平等、更平權的方式合作,促成文化生產上的民生化。[6]

不過,這種主觀意願可能只是一種尚待發展的理想。劇場體制從來不易打破,疫症只是為社會製造一個「懸置時刻」,令人必須思考改變的可能。可是當疫症過去,或疫症變成「日常」,這種懸置的集體經驗就會慢慢消失,人們返回「正常」、重建「體制」的保守主義聲音就會重新出現。這跟任何社會變革所必須經歷的陣痛,恰恰是相同的。

[1] 凌志豪:〈網上製作的隱喻:對劇場價值以及未來的焦慮〉,《Artism Online》2021年10月號。https://artismonline.hk/issues/2021-10/489

[2] 凌志豪:〈疫情之下的網路劇場:關於媒體的文化政治及新類型的萌芽〉,「國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)」網站,2020年7月15日上載。https://www.iatc.com.hk/doc/106376

[3] 凌志豪:〈疫情之下的網路劇場:關於媒體的文化政治及新類型的萌芽〉,「國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)」網站,2020年7月15日上載。https://www.iatc.com.hk/doc/106376

[4] 凌志豪:〈雲端上的劇場:遊戲、互動式電影與劇場的邊界〉,「國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)」網站,2021年7月12日上載。https://www.iatc.com.hk/doc/106583

[5] 甄拔濤:〈一場意外的去中心實踐:談二〇二〇年的網上演出〉,載陳國慧、朱琼愛、黃麒名編,《香港戲劇概述2019、2020》(香港:國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會),2022)。

[6] 肥力:〈從網上演出思考香港能否發展文化民主〉,「國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)」網站,2021年2月23日上載。https://www.iatc.com.hk/doc/106521

二〇二〇年年初,新冠肺炎爆發並肆虐全球,各地政府採取的種種防疫政策,雖有助減少疫情造成的人命傷亡,但同時百業也必須停擺,市民生活大受影響。香港作為經貿及文化往來頻繁的國際都市,自然也難以倖免。不少行業在沒完沒了的限制成了常態之時,逐漸開始發展出各種應對策略,在疫情反覆下盡力渡過難關。為免防疫政策過度影響經濟活動,香港政府在限制社交距離的同時,也有向因工作需要而必須群聚的人士提供豁免。

惜這項豁免並不適用於劇場工作者。雖云疫情緩和之時,劇場也被容許有限度恢復演出,然而對香港劇人而言,反覆不定的疫情帶來的並非一種可勉力招架的所謂「新常態」,而是擺盪在全面停演與部分復演之間的永劫循環——舊一波疫情退潮,只意味著在新一波疫情來襲前,必須盡速完成製作並及時送到劇場上演,令人無所適從。大概只有理解劇人自疫情爆發以來那如情緒過山車般的經歷,才能真正明白表演藝術行業在疫情下不單遭逢多次停演的重大打擊,也在戰兢的創作中與不確定性角力,盼望最終能逃過演出夭折、努力付諸流水的命運。

也只有在這個背景下,我們才能明白,二〇二〇年以來興起的線上劇場,遠非一種時興的玩意,而是銘刻著在艱難時代下求存的印記,從中我們不但可窺見劇場工作者在理想和幻滅之間的掙扎,更能深深感受到他們如何在創作過程中迸發出驚人的適應力,並展現其對戲劇藝術擇善固執的精神。

在兩次深入訪談中,四個香港表演藝術製作團隊的代表,分享了自身在疫情期間製作線上劇場的經驗。各團隊擁有的製作資源及採用的美學策略均不盡相同,故此他們各自呈現的「線上劇場」面貌也各不相同。這些寶貴的經驗分享,當可讓我們更了解香港劇場如何面對現實難關,摸黑尋得一條又一條出路。

雖同被冠以「線上劇場」之名,但在疫情前投石問路、只留下模糊足印的零星之作,與疫情爆發後大行其道、透過密集實踐而漸見類型(genre)輪廓的演出,實難相提並論。如前所述,催生這次線上劇場風潮的第一因,與其說是主動積極的探索,不如說是現實的逼迫。然而現實中的不幸與無可奈何也有千百種,要探究其路向,便必須了解線上劇場這個「替代方案」,如何成為在不同劇團在現實中的創作出口。訪問中幾位劇場工作者的分享,相信可讓我們更深入了解不同團隊當初製作線上劇場的出發點,藉以進一步把握他們各自發展出來的美學構想。

對於委約製作來說,最後拍板決定權非在劇人一方,故這類製作團隊的情形可說是最為被動。如香港藝術節委約表演製作《鼠疫》(粵語版)的劇場導演陳泰然便表示,他從來都以在實體劇場表演為首選,排演時得知主辦方因第四波疫情而決定改成線上演出後,仍極力爭取在劇院作現場演出,惜無功而還,只能按委約方要求,將表演拍攝下來並放到線上供大家觀賞。

香港藝術節《鼠疫》(粵語版)

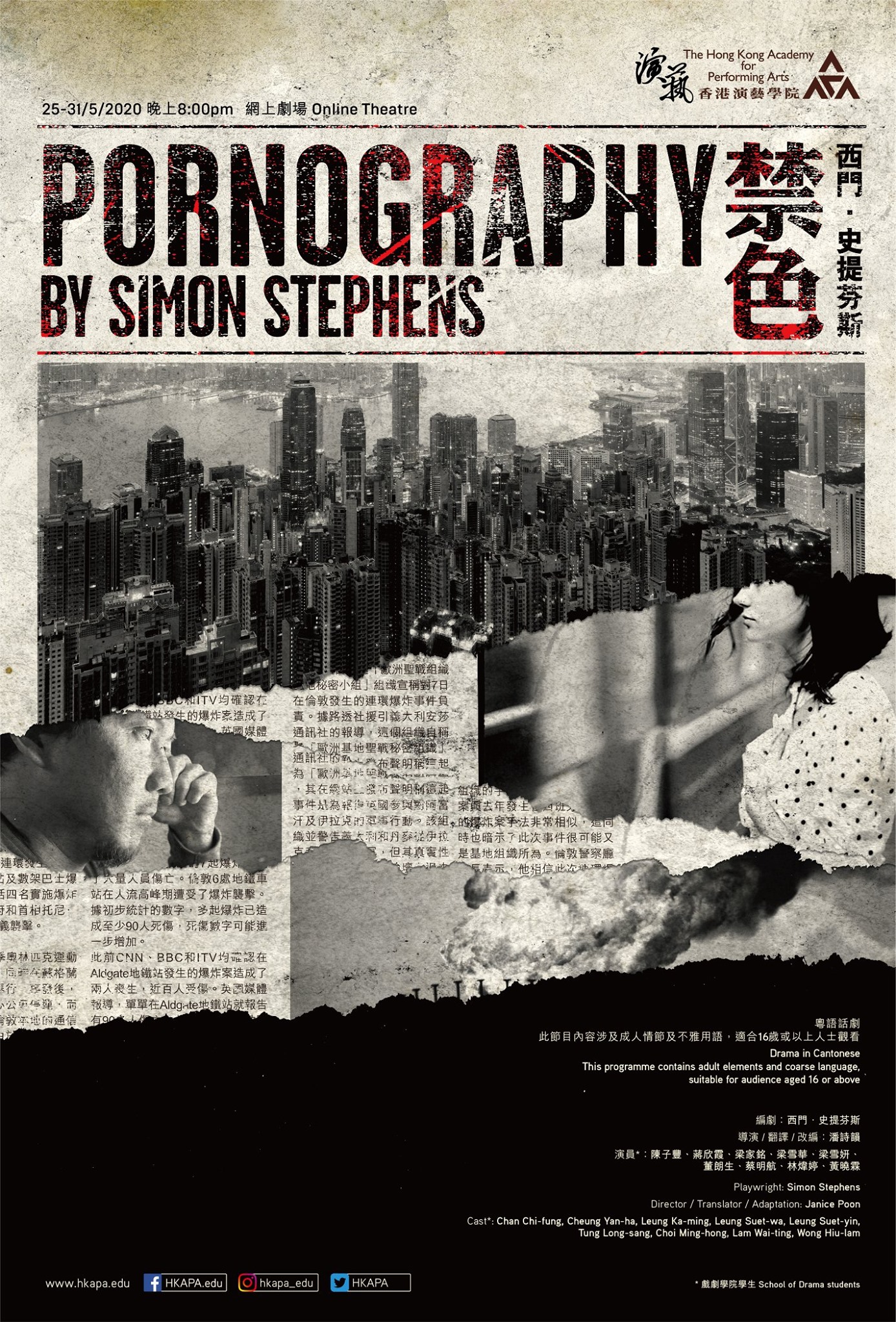

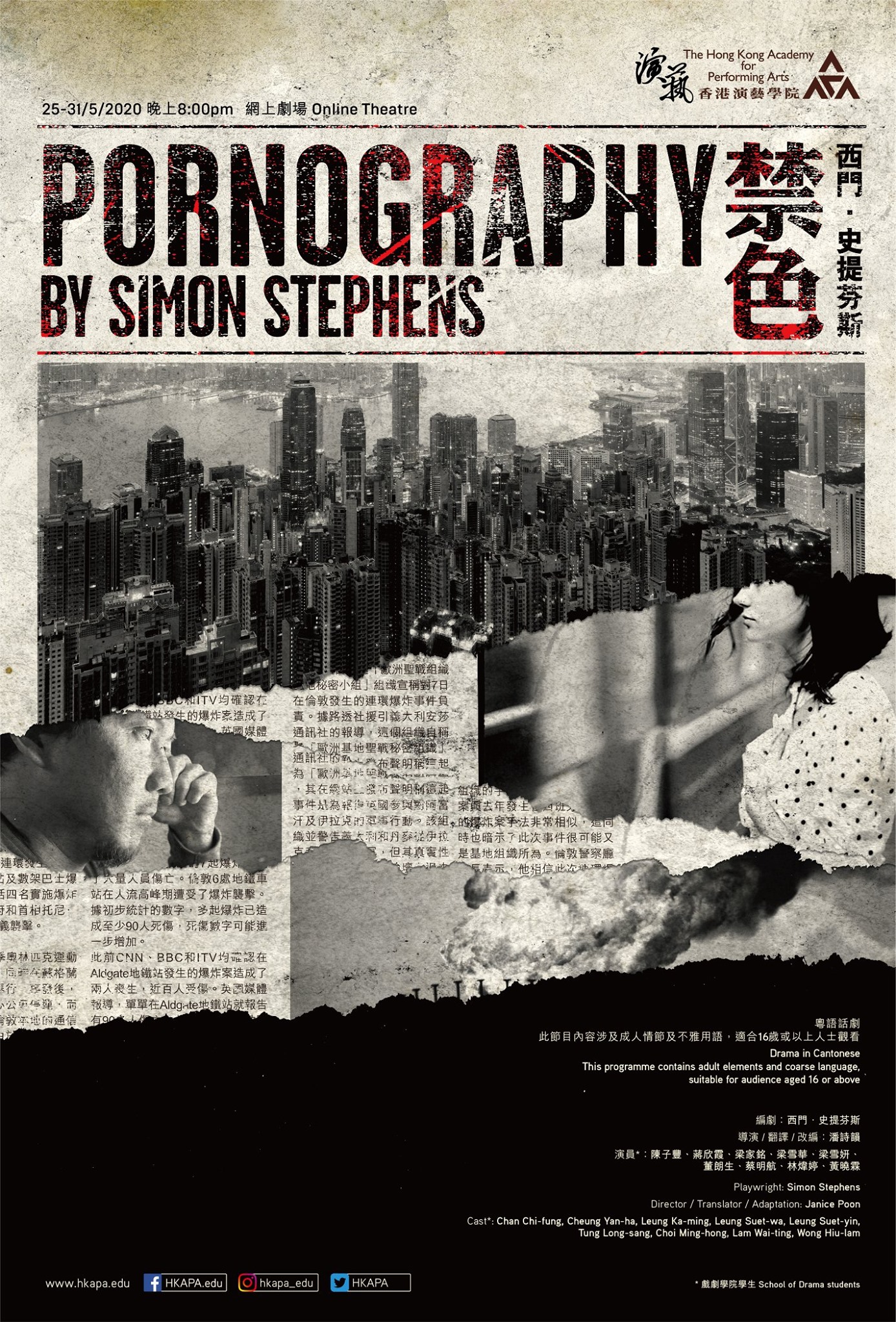

另一個較為普遍的情況,則是團隊在製作過程中得知作品無法在劇院上演後,因不願白白埋葬創作心血,故在直接取消節目和轉到線上演出兩者之間,無奈選擇後者。如同流劇團的《巴黎公社的日子》(下稱《巴黎公社》)導演鄧偉傑便憶述道,二〇二〇年中得知因疫情限制而無法進行現場演出,惟當時作品的排演進度已達四分之三,故因不希望浪費已付出的創作成果、錯失探討布萊希特劇場美學的機會,最終決定將演出拍攝下來,並以錄播形式呈現給觀眾。同樣,由香港演藝學院製作的《禁色》之導演潘詩韻也表示,是次表演為學院畢業班同學的課程,作品本來安排在學院的劇場上演,惟疫情爆發後學院學生必須留在家中,她詢問同學的意見後得知各人仍想繼續學習,故決定轉而將表演安排在線上實時進行,並於二〇二〇年五月底完成演出。

相比之下,香港話劇團《原則》二〇二〇年重演版團隊的創作原委及經驗則稍有不同。演出本來安排在該年九月底至十月進行,惜七月香港不幸出現第三波疫情,八月底疫情雖已趨緩、各種防疫限制也逐漸放寬,惟當局遲至十月方重開劇院,容許劇團在座位減半的情況下恢復演出。劇團無奈必須取消九月底的場次後,終能在十月初恢復進行現場演出,並同時決定推出線上直播版,為觀眾提供另一種欣賞表演的角度。香港話劇團高級經理(製作)黎栩昕解釋,希望可以讓更多觀眾接觸該作品,故決定另外加入串流直播的觀看選擇,以線下線上並行的形式呈現表演。然而,該劇導演方俊杰也坦言,自己始終以照顧劇院現場觀眾為首要目標,足見大部分劇人的首選,仍然是在實體劇場進行表演。

無論決定製作線上劇場的原因為何,反覆無常的疫情令各劇人皆手足無措,似乎大家當初主要仍是以兵來將擋的心態進行製作,故想法較傾向將線上劇場視為是一種權宜之計,也因此製作上多希望以一種「還原劇場」的方式處理演出。的確,實驗性背後是長期的思想與實踐的醞釀,非一時三刻可以完成,與其不切實際地期待疫情能瞬間為線上劇場提供大量創作契機,不如待那注定是帶點倉促的創作完成後,積極汲取經驗,為下一次演出作準備。

然而我們都知道,創作藝術的基本要求是對工具的熟知,要談得上還原,必然無可避免涉及技術層面的試驗及實踐。正因為如此,各團隊均也有在創作期間,進行過不少對拍攝技巧的摸索。劇人在訪談中,便與我們分享其如何各施各法,在未知的領域進行各種技術摸索。

如鄧偉傑就表示,《巴黎公社》拍攝一些演員較少的場景時,並沒有只限於選用錄像攝製慣常採取的「三機擺位」拍法,而是希望在鏡頭擺位上多花點心思。《原則》拍攝導演何小寶也指,自己特地為線上版設計了兩個獨特的攝影角度,其鏡頭分別位於舞台正上方及觀眾席面向舞台的正中位置,用以突顯劇中一些現場觀眾未必能察見的細節。同樣,《鼠疫》錄像導演吳卓昕亦解釋,她在拍攝演出時特別選取了較為寬闊的影像長寬比,有別於一般電影16:9的比例,藉以在取景時更能捕捉到表演場地的實際戲劇活動。

對於一些資源較為緊絀,但創作壓力相對較小的製作團隊而言,這種往往必需花費大量時間的摸索雖難免步履維艱,但同時也可能帶來一些意外的創作驚喜。《禁色》便在這方面給我們提供了非常值得參考的創作經驗。潘詩韻提到,學院雖然批准了將《禁色》改成在線上演出,也在宣傳及相關方面提供了充足的支援,但整個製作均由他們一手包辦,表演場景就是參與演出同學的家居空間,故可說是「零成本」的製作。她又補充指,同學們花費了不少精力,摸索如何在線上平台轉換場景,以至加入特別視角效果等的技術,幸而最終都藉著掌握平台的特性及多次嘗試,成功呈現他們希望帶給觀眾的演出效果。

這些從製作線上劇場而來的技術得著固令人感到欣喜,惟如前所述,以線上暫代線下本身便是種非常時期的非常手段,故劇人無可避免必須以一種「山寨製作」的精神,靈活地應對現實工作環境帶來的種種巨大限制。如果說《禁色》製作的挑戰之一在於演員必須就地取材,那麼同流《巴黎公社》的拍攝工作,則道盡在劇場錄製影像的難處。鄧偉傑表示,由於決定在劇團的排練室進行拍攝並在現場收音,故必須把冷氣關掉,惟當時正值盛夏,演員在拍攝時的辛勞可想而知。此外,排練室又位處工廠區,故須待下班時間後環境變得較寧静時,方能開始拍攝工作,因此演出及攝影往往會持續至晚上。《鼠疫》的拍攝難處同樣包括劇場的地理位置問題,如陳泰然便憶述,他們到了排演後期,才知道被安排在牛棚藝術村的劇場進行拍攝,必須在短時間內設法將場內的鐵柱融入到場景設計中。吳卓昕也表示,由於牛棚舞台的深度不夠,故必須盡量避免以遠景進行拍攝。

同流《巴黎公社的日子》(來源:同流Facebook專頁)

相對而言,《原則》雖說是在傳統的實體劇場作現場演出,線上版驟眼看來只是錦上添花的附加選項,但團隊同樣面對另外一些來自串流直播的挑戰。如何小寶就解釋,雖然現今拍攝機器相對已較便宜,但由於有觀眾在場,無法在演出進行期間移動攝影器材,故他必須事先「種植」不同位置,在劇院各處放置多部攝錄機。黎栩昕亦表示,為確保觀眾可以順暢無阻收看直播,必須事先聯絡網路供應商以取得充足的線路頻寬。此外,她又表示線上劇場必須解決不少版權問題,並解釋香港話劇團挑選了《原則》作線上直播,而非當時因為疫情而被迫停演的翻譯劇《父親》,其中一個重要原因就是後者本身已有電影改編版,故此幾乎不可能取得劇作的線上播放版權。同樣,她解釋必須為劇作中播放的音樂取得網上播放版權,故若要將一部採用大量流行音樂的劇作轉成線上演出的話,涉及的費用可能不菲,令製作成本大增。

戲劇與電影雖同屬表演藝術,但「隔行如隔山」,兩者各自的預設觀看模式實難作比擬,吸引的觀眾群也不盡相同。對創作人而言,形式上的轉化遠非止於學懂如何駕馭上述與拍攝器材或視訊會議有關的技術,而是必須深入虎穴,叩問及疏理兩種藝術的異同,並從中覓得自己的定位。

同樣,若然只是添加一個名為「線上」的標籤,便理所當然地期望觀眾自動從一種既有的觀演模式,過渡到另一種連創作人自己都仍然在摸索的觀演/映模式,則難免顯得一廂情願。幾位受訪劇人便跟我們分享了他們在製作線上劇場的過程中,怎樣處理與當代觀看文化接合時所遇到的挑戰,包括如何藉著重新思索劇場獨有的觀看模式,在錄像的殘影中留下一絲揮之不去的對「現場」的追憶及想望。

要創作出一部具有美學連貫性的作品,團體成員自身之間無疑必須首先形成基本共識,劇場與拍攝或錄像導演之間對演出媒介之定位也須保持一致,對以線上劇場為唯一表演媒介或「產出品」的團隊來說,則更自不待言。

如導演希望影像盡量翔實地記錄劇場的話,則如鄧偉傑所言,舞台和視像導演的溝通應要增加,從而確保舞台演出和錄像的差距不至於過大之時,又能保留舞台感。吳卓昕同樣指,導演之間必須有溝通,並表示明白自己負責的是「輔助」部分,即如何活用電影或鏡頭的語言,準確捕捉劇組整體創作。然而在時間催迫下,劇場導演便要與此前在戲劇製作中絕無僅有的拍攝或錄像導演迅速完成磨合,談何容易?

同樣,演員面對線上劇場這種新媒介,也必須花時間適應及調整自己的表演方式及心態。確實,習慣在眼見的時空中表演的戲劇演員,在舞台前架設好攝錄機後,並非便可輕易搖身一變,在鏡頭前若無其事地繼續演出,而是往往會有各種疑惑,無法估量其演出將如何被呈現在屏幕之前。要克服演員及製作者的心理關口,劇場工作者之間的溝通合作必須變得更緊密——正如吳卓昕所言,大家要一起看、一起討論,再考慮哪一種做法會較合適。當然,專業演員在鏡頭面前,往往就如潘詩韻所指,總是能不斷地適應舞台和錄像兩者間在節奏上的差異,並作出相應調整。

創作團隊尚且能在排演及後期製作階段憑著溝通與交流,共同發掘兩種形式交錯下產生的可能性,但相比之下,劇人卻無法控制觀眾如何接收演出影像,只能透過自身對當今媒體文化的觸覺,捕捉觀眾的觀看之道。媒體理論家奧斯蘭德(Philip Auslander)認為,現在所謂的現場演出已全面被媒介化,身處劇院的觀眾也只能藉由媒體觸摸現場;我們大可不必完全同意其稍嫌武斷的觀點,但也必須認知到無所不在的媒體對我們的影響,而觀眾在這個充斥視聽資訊的媒體世代,則只能往往以既有的消費媒介方式為據,有意識或無意識地將之歸類到自己熟知的領域。

比如說,觀眾實際在屏幕前觀看演出時究竟會有多少專注力,便成了製作線上劇場時必須仔細預估及考量的重要一環。如方俊杰便提到,觀眾在劇院現場觀看演出時,較能在轉場期間的瞬間暗場(blackout)之際靜心等待,但一旦轉成視像版,便無法立即習慣瞬間暗場,彷彿總希望舞台在變暗後立即進入下一幕。他總結道,劇場和電影的觀眾始終不同,劇場觀眾的參與度較高,電影觀眾的接收則較被動。同樣,吳卓昕以拍攝《鼠疫》時如何處理當中的轉景為例,說明觀眾看戲劇和電影時的預期有何差異。她解釋,觀眾固然清楚地意識到自己在觀看以視像形式呈現的戲劇演出,但往往仍會不自覺在瞬間切換成看電影或電視的慣常觀影模式,耐性也隨之變得很有限,這也令她在拍攝過程中感到掙扎,反覆思考應以電影常用的跳接方式處理轉景,還是該盡量保留舞台上的每一刻。

如何處理這個媒體「錯位」的問題,並重新定義或確認自己的目標觀眾,也許最能顯示不同劇人在線上劇場上的取態有何根本差異。如《原則》的製作團隊便傾向將串流直播及其後於戲院播放的錄製版,視為劇團拓展觀眾的方式之一。如方俊杰就表示,他認為《原則》線上版並非要取代實體演出,而是可以透過影像傳播,吸引更多觀眾日後進入劇場觀賞現場版本。故此對他來說,線上版的主要作用是配合現場演出,宣傳意味多於一切,並坦言其團體畢竟並非以製作自足的《原則》電影版為目標。黎栩昕亦指,有不少曾在進場觀看《原則》舞台劇的觀眾在看過電影版後,會反映說能在影片中觀賞到演員的細緻表情及情緒反應。故此,透過電影附加版本,劇場觀眾能夠彌補當初在現場錯過了這些細節的遺憾,影像版也因此算是建立在現場表演基礎上的一種「補完」。

這種以「還原論」為首要目標的線上劇場製作實踐,自然是處理線上劇場觀看模式的一種可能。確實,不少受訪者在訪談中念茲在茲的,是對於「舞台感」(鄧偉傑、吳卓昕語)、「劇場的味道」(方俊杰語),或「劇場感」(何小寶語)的關注或追求。對這些劇人而言,製作線上劇場的初衷是透過影像還原現實中的劇場空間,也因此對他們來說,當務之急是探討如何在數據傳輸中保留劇場的感覺或味道,在不完美的影像媒介下盡量呈現現實劇場的色彩,努力將劇場的「現場感」、「轉瞬即逝性」、「觀演互動」等特性保留下來。

具體而言,這些受訪團隊主要透過拍攝及後期製作的針對性處理,在影像的傳輸或拍攝過程中刻意保留劇場的慣習,藉以留住劇場色彩。如鄧偉傑便為上載到網上的《巴黎公社》演出影片設下觀賞期限,並解釋此舉與觀眾在現實進入劇院時必須遵守特定規則的情況相若,兩者均與劇場文化有關。除了透過劇場獨有的儀式感喚起觀眾的認同外,《巴黎公社》的影片本身亦與普通電影不同,未有在錄像開首或結尾加入影片標題及製作人員名單,刻意與電影典型的自我呈現保持距離。同樣,《原則》串流直播版本也在開場前特意拍攝觀眾魚貫入座的情況,除了能讓大家目睹疫情下觀眾席呈現的特殊景觀外,我們也可以將之理解為將屏幕前的觀眾帶到劇院,邀請線上觀者與現場觀眾同呼吸的一種嘗試。

藝術貴乎多元,觀眾固然與珍視現實劇場的創作者一同引頸以待,期盼疫情結束後能盡快重新迎來全院滿座的一刻,但我們在這次對演藝界而言有如例外狀態般的失重創作環境中,也得見不少傳統劇場工作者順水推舟,利用這次特殊的線上劇場熱,在大眾媒體領域上下求索,並推出了不少充份利用媒體作為創作主軸的線上作品。

自二十世紀初大眾媒體興起至今,形形式式的媒體早已跟大部分人的日常交織得難分難解,故媒介化的表演確值得我們加以探索。真實得往往只淪為時髦語的「媒體即訊息」(the medium is the message),便說明了媒體如何逐漸融入我們生活當中,以無所不包的臨在方式統攝我們的感知。面對媒體那來勢洶洶的天羅地網,劇人反其道而行,將作品轉化成一種游走在流行媒體間、在重重折射中伺機重構虛擬與現實時空的演出,見證了戲劇界如何探尋媒體在表演藝術上的可能,也體現了劇人在創作中廣納百川的開放精神。

藝術創作總是環環相扣,新科技帶來的從來都不單僅是創作藝術工具上的新選項,也同時迫使創作人再次擁抱混沌。劇人必須仔細入微地重組傳送—接收過程中的一磚一瓦,並從中思考藝術作品的整體形式及其美學指向,其構想的深刻程度遠超所謂以科技加持藝術一類的淺見。事實上,單是從默片過渡到有聲電影的歷史,便不單見證了演員的聲音如何魔幻地出現在本來只有動作及表情的電影,也讓我們觀察到表演藝術如何牽一髮動全身,促使製作人必須摒棄過往行之有效的創作策略,重新思量敘事以至演員表演方式在新媒體下應扮演的角色。

故此,我們在創作時無可避免必須徹底撇除一切有關媒體類型的先見,以最處境化的角度考慮媒體各自獨有的敘事空間及其與演員演出之間的張力。正如陳泰然在分享《鼠疫》拍攝過程時所言,遇到如演員是否該看鏡頭這類涉及戲劇—電影語言交錯的情況時,他必然會以戲劇構作的整體角度作判斷,而非只是架空創作現實,單純只考慮技術問題。

又如潘詩韻在分享《禁色》製作過程時所言,我們必須留意觀眾實際是在採用何種視角觀看演出,因為對她而言,必須將演出的線上平台自身視為一個自足的舞台,並弄清楚其美學特色,包括演員與觀眾如何在平台建立觀演連繫。也正因為如此,她以大眾於疫情期間在家觀看Netflix的慣習為參照,透過將演出分成七集上演,把作品轉化成一部一連七晚播放的連續劇。她續指,每種藝術形式均有自己的特色,故此沒有所謂誰取代誰的問題,也不應去考慮如何適應(adapt)電影語言,反而應多思考如何充份利用特定平台或媒體的特性進行創作。

香港演藝學院《禁色》——西門.史提芬斯

然而,看上去希望保留「劇場感」的製作團隊,主要著眼點雖為傳統劇場,但這並非便必然代表著一種拘泥於既存體系的保守創作態度。如鄧偉傑分享《巴黎公社》的製作過程時,便憶述自己當時曾有好幾次在思考甚麼才是舞台感,並認為是否應保留如瞬間暗場一類構成傳統舞台的部分,實在很取決導演希望如何在舞台上詮釋劇本。他舉例說,那半至一分鐘的瞬間暗場可能是留給觀眾進行思想沉澱的機會,並指如果我們以這種角度作考量的話,保留該段沉默的時間便變得異常重要,而非因循守舊的做法。

循鄧偉傑的看法推演,我們甚至大可將這種在影像中呈現一些在畫面中看似格格不入的傳統劇場實踐,視為是主動形塑劇場觀看模式的嘗試。此舉雖可能令看慣當代緊湊剪接影片的觀眾感到突兀,但從另一個角度看,不啻是一種形式上的「種植」,也是主動形塑觀看文化多樣性的嘗試,故當然也應被視為是另一個層面的實驗和藝術實踐。

或許,我們應當策略性地發展一些新詞彙,藉以令劇人及觀眾在談論線上劇場創作時,能更精準地指向相關的藝術關懷。如陳泰然便指,從理解電影和舞台兩者關係的角度看,《鼠疫》只是一個十分初步的嘗試,並認為電影始終是一套十分特定的語言,甚至不應被視作是慣常定義下的語言。又如訪談中何小寶提出「混合媒體」或潘詩韻提出以「鏡頭語言」取代「電影語言」等,均是超越戲劇—電影兩者間非此即彼的關係,以及探究媒體藝術各種可能性的嘗試。

另一方面,創作者無論是偏向以媒介還原劇場,還是較希望探索媒介如何可以反過來重構演出,劇本作為戲劇的骨幹,在媒介化的線上演出中仍是個舉足輕重的創作元素。在當代劇場百花齊放的劇本題材及紛陳的敘事策略上,如何看待媒介與劇本結合的問題,也十分講求劇人的眼光及判斷。

如方俊杰便以《原則》為例,指出由郭永康編寫的劇本並非一部只敘述單一時空的實時劇作,而是涉及一種時間上的過渡,故需要一個較廣闊的視角處理創作,藉以產生一種「劇場的味道」。問及哪些劇本較適合在線上呈現時,他認為有較多過場及瞬間暗場、需頻繁轉景一類的作品,較不適合作拍攝。鄧偉傑則表示,因《巴黎公社》的畫面和敘事變化較複雜,自己特別要求呈現三個特別能突顯布萊希特劇場特色的畫面。潘詩韻則表示,《禁色》的劇本語言十分強烈(intense),甚至有近乎詩化的語言,人物的感情濃烈非常,每一場均為獨白或雙人戲,拿捏得不準確的話,便很難呈現人物的處境,故也必須按情況選取合適的鏡頭。

談到這次線上劇場的美學實踐特色,我們當然不能忽略「沉浸式劇場」及「互動劇場」這些受不少劇人青睞、甚至儼然成為了線上劇場的主要詮釋及創作方向的時興標籤。然而,與其一窩蜂製作過份賣弄單一概念的藝術作品,似乎我們更應在線上劇場的發展方興未艾之時,回到「劇場是甚麼」的根本問題。如上文提及對戲劇感的追求,及對媒體特性的探索,均可被視為是觀照戲劇本質的嘗試,而非因為一時的創作焦慮而選擇迎合市場。

陳泰然便觀察到,不少劇人在製作線上劇場時,彷彿被迫走出自己的創作安舒區,接觸一些平素沒有觀看自己作品的觀眾,並指不少創作者仍顯得有點著急,彷彿急切希望尋得一種萬靈丹,藉以確保演出可以找回劇院那上千人的目光。他表示,自己作為一個藝術創作者,最重視的還是如何可以製作出一種美學上的形式(pattern),以及如何最終令觀眾有美學上的得著。

展望將來,如果說這次的線上劇場熱,說到底不過是種缺乏選擇下發展出來的權宜之計,那麼疫情後的線上劇場又將何去何從?我們在此再次看到劇人的不同想法及其各自的創作關懷。如鄧偉傑便表示,線上劇場有很大發展空間,但坦言作為創作人,仍最希望在實體劇場空間進行創作。潘詩韻則認為,線上劇場不應單是一種解決疫情期間創作問題的應對方法,而是個可以供大家長久創作的舞台,她認為只要形式和內容可以緊扣的話,其實不同類型的作品均可透過線上劇場形式呈現。吳卓昕亦認為,現在很多人的心態有點本末倒置,似乎是因為疫情期間不能製作舞台劇,故才嘗試涉足線上劇場,而不是打從一開始便以媒體融合的角度進行創作。

但無論劇人創作取態為何,相信線上劇場還是有其獨有的存在價值。訪談中,不少劇人均提到如何充分利用線上劇場跨時空的特質,將戲劇延伸至海外並呈現給各地觀眾,或是透過資料庫的形式,為過去曾上演的演出注入第二生命。

黎栩昕便指,《原則》有兩至三成的觀眾來自外國,可見有不少海外觀眾均有興趣觀看香港劇場演出,並指會在日後研究在劇團資料庫內,挑選一些作品並將其以線上形式呈獻給大家。方俊杰也認為,香港觀眾開始接受上網觀看特定節目必須付費的安排,冀望業界人士將來可以共同建立一個平台,把自己團隊的作品上載到網上,為香港劇場表演創建一個資料庫。進一步而言,劇場既為我們共有文化記憶,亦可助我們建立一種新的跨地域劇場文化。如陳泰然便表示,越來越多人到不同的地理空間生活,故此不受地理環境限制的線上劇場,可讓我們思考究竟劇場可以如何存在於這些人之間。

然而虛擬空間提供再多的可能性也好,總仍難免受現實物質條件的制約。製作線上劇場往往所費不菲,故此其創作實踐亦得有相應的財政支持作為創作資源,方能在日後繼續順利發展下去。如方俊杰便坦言,從財政收支角度而言,製作線上劇場在此刻無疑是不划算的,並明言分別只是虧多還是虧少。陳泰然也指,如果需要進行串流直播的話,便必須安排各種配合的器材及人員,成本無可避免會大增,也因此早在製作之初便已排除了直播的選項。

著名的國際文學理論家和樂評家愛德華.薩依德(Edward Said)曾在〈極致瞬間〉一文中,批評當時的古典音樂會如何僵化:

「兩小時的古典音樂會已經『凝固』為一成不變的商品,……,對於『表演體系』的標準化規定可謂事無鉅細,面面俱到—包括衣著、曲目安排、演奏者的行為舉止、演奏風格、觀眾的行為、票價的制定、演出形式、表演者的身份,等等。….最無趣的表演幾乎無一例外來自於那些乖乖接受兩小時不自然的拘限,毫無怨言地做機械肢體活動的音樂家。」[1]

薩依德大抵沒有想到三十三年後的全球新冠疫情,才促進全球樂團思考音樂演出的其他可能性。本文以此作引言,並以「疫中作樂」為題,旨在寄語全球疫情雖令香港音樂藝術工作者面對業界寒冬,但他們的堅毅和對音樂的熱誠令他們捱過每一波疫情。而這種疫中作樂的智慧更在他們如何應對每一波疫情中突顯出來。

新冠疫情自二〇二〇年起至今仍未結束,因疫情未有消退和受到香港政府《預防及控制疾病(規定及指示)(業務及處所)規例》(第599F章)有關公眾娛樂場所條文的限制,香港藝術團體暫時最多只可以銷售場地85%座位的門票。除此以外,香港藝術界分別在二〇二〇年連續受到四波新冠疫情的衝擊,平均每季一次。而每一波疫情都會在一至三星期內引發表演場地關閉,令業界不止疲於奔命,更令生計大受影響。縱然政府有直接發放資助支援自由藝術工作者,但資助最多那一次也只有一萬港元。雖然雪中送炭,但若以香港政府統計處2019/2020 每月平均住戶開支達三萬零二百三十元[2]作指標,只能說是杯水車薪。而香港舞台藝術從業員工會曾於二〇二〇年七月向約四百名會員進行「有關受疫情影響及抗疫援助成效」問卷調查,「結果顯示接近四成人沒有獲得政府任何補助。」[3]。毫無疑問,政府在平衡公共衛生安全和行業生計明顯仍有很大的改進空間。

然而,疫情為全球藝術界帶來比金融海嘯破壞力更強的災難,但同時催生網上演出的機遇。縱然大環境處處受限,但不少香港藝術工作者仍本著「獅子山精神」,在有限資源下探索了表演形式數碼化、藝術科技的可能性、觀眾拓展、收費模式等等。即使成效不一,但至少也是整個行業拓展數碼化的一個重要契機。

「演上線」計劃乃是國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)網上年鑑系列一個延伸。理念之初是希望為香港藝術發展在疫情之中所遇到的網上演出問題和相應的解決方法作一個紀錄,並深信這些紀錄能夠為香港藝術團體日後如何發展數碼演出和資產作參考。值得留意的是,在各波疫情之中,第五波疫情實施最嚴厲的關閉表演場措施,霍啟剛議員也曾在立法會向行政長官反映文藝界「沒有地方練習和錄影」[4],可見第五波嚴厲社區隔離措施已令香港藝術界網上演出大受阻礙。然而,由於第五波疫情不在本文篇幅以內,所以不作探討。本文主要就香港音樂藝術界在二〇二〇年至二〇二一年網上演出第一至四波疫情發展,不論在演出形式、數碼技術、平台發佈和曲目選擇等方面作出分析。但在分析前,先要討論一下全球現有網上音樂會演出模式,並分析當中利弊,為下文每一波疫情的分析建立一個理論基礎。

網上音樂會在疫情前已在發展中,但並未成為主流。其實早於二〇〇七年蘋果便推出「蘋果音樂節」,以先直播,後串流放映,免費讓Apple Music 及iTunes 用戶欣賞。

二〇〇八年,柏林愛樂開展了「數碼音樂廳計劃」,並於二〇〇九年一月現場轉播第一場高清音樂會。二〇〇八年至二〇一六年間德意志銀行為主要贊助。柏林愛樂在準備此計劃時,把音樂廳規劃成一個專業的錄影棚,加設六部高清攝錄機及控制室,讓技術人員可以在直播時即時轉換畫面。在疫情期間,更升級所有設備至支持4K和HDR格式 。而數碼音樂廳採取混合收費模式,觀眾可以選擇訂閱一星期、月費或年費,豐儉由人。

二〇〇九年一月,YouTube 開展了YouTube 交響樂團計劃,鼓勵全球古典音樂樂手提交音樂錄像以獲邀到美國卡內基音樂廳演出,更有趣的是YouTube 用戶可以投選他們喜歡的樂手到美國演出,這也是現場音樂會未能做到。而譚盾《第一互聯網交響曲「英雄」》也結合了遴選者的錄像於YouTube 發佈。二〇一一年YouTube 交響樂團移師到澳洲悉尼歌劇院舉行,並進行免費網上現場直播,更特別要求每位樂手即興演出一段音樂。二〇一一年YouTube 交響樂團的悉尼演出是由Hyundai 現代汽車贊助,演出片段也於演出後五天內得到全球三千三百萬人觀看[5]。

由以上可見,網上音樂會早在十多年前已開始發展。由於製作目標不同,也分別發展出不同的收費和免費的模式。但不論那一種模式,也需要有贊助商支持,並相信音樂這個世界共同語言能夠為他們帶來全球曝光率才能得以發展。而以上這些模式,部分在疫情之中以其他方式出現。

那麼香港樂團在疫情前如何發展其網上音樂會?本文希望在探討香港樂團每一波疫情如何應對前,先討論究本地樂團在疫情前是否有足夠資源、人材和技術去發展和管理數碼資產。文中的數碼資產指樂團任何可供觀眾欣賞的數碼制作,不限形式及網上發表平台。香港音樂藝術界在疫情前已開始發展網上音樂會或音樂會前講座,大多都是採用免費模式,現列舉部分活動如下:

| 日期 | 樂團 | 網上直播音樂會/活動 |

| 二〇一七年三月 | 香港弦樂團 | 《超時代音樂會 - 譚盾》音樂會前安排「譚盾100面對面」免費在YouTube 和優酷直播 |

| 二〇一八年一月 | 香港小交響樂團 | 第一屆香港國際指揮大賽設免費網上直播 |

| 二〇一八年九月 | 香港管弦樂團 | 《風格配樂大師:馬克斯.李希特》在九月一日演出後免費分享錄影片段; 與Deutsche Grammophon 合作,唯剪輯後的片段現只於Deutsche Grammophon YouTube頻道放映 |

| 二〇一九年一月 | 飛躍演奏香港 | 比爾斯飛躍演奏音樂節「情迷探戈」音樂會; 與美國The Violin Channel 合作,並安排免費網上直播 |

所以香港音樂藝術界在疫情前已開始嘗試安排免費網上音樂會,但未大力發展任何收費模式。然而疫情前,香港樂團若要發展網上音樂會也會面對場地配套、攝影器材及人才、成本收益、平台發佈和觀眾拓展這五方面的問題。筆者在二〇一九年安排網上古典音樂會直播時最大挑戰是音樂會場地並沒有架設寬頻線,即使另外鋪設,也所費不菲。更甚的是,不少場地設計是難以接收網絡訊號,再加考慮上音樂廳聲效,合適做現場直播的音樂廳其實少之又少。二〇一九年若要在一個月內安排網上直播並有穩定網上串流的音樂廳,首選必然是香港大會堂音樂廳,但我們只可用4G LTE 行動Wi-Fi分享器,並使用流動數據把音樂會錄像於網上發佈。若電訊公司的網絡不穩定,也會影響到音樂會串流質素。另外,疫情前香港仍未形成網上節目收費的環境,而租用攝影團隊和器材並不是一般藝團能夠恆常負擔,所以只能選擇免費播放作觀眾拓展,因此網上音樂會並非香港樂團首要發展項目。硬體上的場地配套和攝影器材或許可以透過資金解決,但如何確保網絡穩定和直播畫面配合音樂轉換順暢,藝術行政人員則需要有網絡串流、剪接和樂曲的知識才可減低網上現場直播「畫面和音樂未能配合」的情況。另外演出前如何處理演出者和平台版權問題,也是一個值得注意的地方。

如果我們借用菲利浦.科特勒在《行銷5.0》指,不論公司和顧客都要具備數位能力才可推動數碼轉型,甚至提出「這場危機(新冠疫情)確實暴露了特定顧客族群和產業業者數位化的準備程度,有些根本缺乏準備。」而香港樂團、音樂藝術工作者及其觀眾正正是菲利浦.科特勒所指缺乏準備的產業。疫情前的香港音樂觀眾主要是享受免費網上音樂會,並未有消費網上音樂會的習慣。而樂團在面對場地設備和人才方面,都未有太多資源大力發展網上音樂會或數碼化。所以不論「九大」[6]還是中小型香港樂團和其觀眾,在疫情前未算有充足準備去應付突如其來的數碼轉型,更遑論香港樂團發展其數碼資產。

若我們向流行音樂生產業借鏡,它們因疫情而大力發展網上音樂會,並為了加強網上音樂會獨有體驗,不論華語樂手林俊傑、韓國樂手Super Junior和美國樂手Billie Eilish 也在線上演唱會加入XR元素,讓樂迷有另一番體驗[7]。KKTIX票務及虛擬場館事業群總經理林怡君也在訪問中分享:「去年疫情爆發之後,海外藝人粉絲見面會或演唱會一下子都沒有了,開始討論轉成線上的可能性。尤其,海外藝人巡迴演唱會都是固定的,一旦檔期取消,曝光量也會減少,勢必得想方設法舉辦活動,線上就是彌補回來的選擇。」而在筆者執筆期間,香港流行音樂會也嘗試發展現場和網上音樂會並行的雙軌制。

從流行音樂在網上音樂會的發展,我們也可以留意到網上音樂會發展趨勢為觀眾提供現場音樂會未能感受的體驗。這可以是香港樂團未來發展的方向,但場地、資源和觀眾是否足夠支撐整個發展卻是一個未知數。

所以下文會在每一波疫情先勾勒出新冠疫情對香港樂團的影響,並以全球網上音樂會的方式為例。本文也會討論每一波疫情限制和數碼資產帶來的機遇,同時也會討論業界在每一波疫情下如何精益求精。

自二〇二〇年一月二十三日發現第一宗新冠疫情,康樂及文化事務署(康文署)在一月二十九日宣布關閉轄下演出場地,香港各樂團,甚至香港藝術節也宣告取消。香港各表演團體在第一波疫情未見明朗下,也採取不同的策略與觀眾連結,從中也發現各樂團的資源如何影響他們應對疫情。而在第一波疫情中,不論九大和中小型藝團,它們未有採取任何收費模式,免費給觀眾欣賞。以下簡述第一波疫情網上音樂會的主要模式:

網上社交平台即時直播

由於當時疫情未限制在非康文署場地進行演出,西九自由空間旁的留白Livehouse仍可安排免費網上音樂會直播,並後來成為#LivehouseAtHome 系列,每逢周五至周日安排一系列本地音樂串流直播表演,帶來爵士樂、另類音樂、古典及獨立音樂的網上表演。「六個星期的 #LivehouseAtHome 串流直播表演錄得全球超過 110,000 人次觀看」[8]。整個系列截至執筆為止,每場演出平均有接近一千次瀏覽,最高瀏覽量的錄影至今錄得四千四百次瀏覽。

樂手在家演出錄影

專業樂手在家演出也是第一波疫情常見的網上演出模式,也樂見不同樂手用不同方式分享他們疫情下的生活和以樂曲鼓勵大眾齊心抗疫。至於在發佈平台上,除了社交平台Facebook 外,也會選擇發佈到其他免費串流平台如YouTube。在這個階段,香港管弦樂團自二月二十日起平均三至四天發佈一段短片,而香港中樂團自三月十二日起每天發佈一段短片。觀眾也對此反應不錯,也多認識了不同樂手鮮有在音樂廳展現的音樂世界,如香港管弦樂團中提琴首席以鋼琴演奏《天空之城》主題曲或香港中樂團笙演奏家魏慎甫在影片演奏《射雕英雄傳》的不同聲部時,不忘加插幽默的「帶頭盔被扑傻瓜」片段。

然而,第一波可以開展此系列的樂團只有香港管弦樂團和香港中樂團,其他香港樂團,特別是沒有駐團樂手的樂團則未有以此方式與觀眾連結。

聲蜚合唱節在第一波疫情下推出第三部「合唱微電影」 一《兩。生》(Double Lives)。由於此影片是香港特別行政區政府「藝能發展資助計劃」的資助計劃一部分,而該計劃早於二〇一七年成功申請。我們很難說這部微電影因疫情而生,但這個形式相比其他網上音樂演出,明顯在視覺上更勝一籌。然而,這部微電影截至筆者執筆之際卻未足五百次瀏覽,實在令人感到可惜。

在第一波疫情下,本地樂手和藝團仍在探索網上演出的各種可能性,不論在形式、曲目和平台均作不同嘗試。縱然以上三種形式之中,微電影不論在整個藝術價值和影片質素上遠勝其他選擇,而且樂曲和舞蹈影像非常連貫,還可以考慮日後於大型屏幕放映。但要留意聲蜚合唱節自二〇一七年起開始籌備這個資助計劃,並不像其餘兩種方式那樣可以即時回應疫情。而網上即時直播和樂手在家的錄影所製造的真實感,營造如布希亞(Jean Baudrillard)在《擬像與擬仿》(Simulacra and Simulation)提出的「超真實」(hyperreality)。這些影片質素不一,如網上現場直播更只是由一個鏡頭拍攝,沒有任何剪接,而且大多只是家用或入門級的專業攝影器材。但這些影片的真實性比真人騷更真實,除了他們有共同以音樂抗疫的信息外,更重要是這些影片大多在非公共空間(留白Livehouse亦非公共空間)或私人地方(如樂手的家中)拍攝。而這種真實感在香港市民自SARS第一次經歷這種大規模隔離後其實有安撫作用,至少令人感到不是只有自己因疫情未能如常工作和生活。相比之下,聲蜚音樂節的《兩。生》(Double Lives)以其合唱學院演唱之蒙台威爾第(Monteverdi)牧歌《狠心的亞瑪麗莉》(Cruda Amarilli)及《噢米提諾,親愛的米提諾》(O Mirtillo, Mirtillo anima mia)為配樂,結合形體和大自然影像所製作的微電影,只能說是生不逢時,其真實性與其他形式實在比下去。然而,這些高質素的錄像製作在餘下的疫情卻大受歡迎,也印證了布希亞的理論之餘,更重要是走數碼化路線不一定要新科技。在合適的時機下,家用拍攝器材也有很好的網上回響。

第二波疫情其實是緊接著第一波疫情,而康文署也於三月二十一日宣布表演場地繼續暫停開放,並於五月二十六日宣佈於六月一日重開表演場地。與此同時,柏林愛樂在三月初便以「贈券」方式,讓全球觀眾可免費透過網絡收看數碼音樂廳推出選自庫存中的特備節目。而美國大都會歌劇院於三月二十日推出免費網上節目系列Nightly Met Opera Streams,每日安排過去十四年曾錄影的節目。在這個階段也突顯了樂團數碼資產的優勢,不單止可以在疫情嚴峻環境下拓展觀眾,更重要是向全球展示其高質素的藝術作品。

這段期間各樂團的在家音樂系列也隨著表演場地重開而結束,但它們和不同商業機構和團體合作,以便進行網上放映。香港樂團網上音樂錄影發佈也沒有較第一波疫情頻密,反而走向電視台節目質素,也進行了不同的探索。另外值得一提的是中小型樂團Music Lab和Live House Wontonmeen合作的一場收費網上直播音樂會《Show Must Go On-Line》,並於Zoom平台發佈以微電影形式拍攝的音樂錄像。相比之下Music Lab 算是疫情之中推動網上收費音樂會的先驅。現簡述第二波疫情不同的合作模式:

香港管弦樂團和香港中樂團在這個時期絕對是表表者,它們分別與3香港合作進行網上直播音樂會。在3香港和其他機構的支持下,香港管弦樂團成功舉辦第一個網上直播音樂會,而香港中樂團則舉辦全港首個5G Live戶外網上4K直播慈善音樂會。這個形式不但滿足了觀眾對真實感的要求,更重要的是讓全球觀眾知道香港的樂團如其他國際知名樂團一樣,有能力舉辦高質素的網上直播音樂會。

香港小交響樂團則是與ViuTV 及MOViE MOViE戲院合作,為香港觀眾帶來“Back On Stage”現場錄影演出,除了做到把音樂帶「入屋」外,更著重錄音及錄影過程達到電影院級數。與其他樂團相比,香港小交響樂團集中資源在高質素的音效和畫面上。

而香港管弦樂團也於六月五日發佈在RTHK 31台《演藝盛薈.音樂到會》的錄影。由於是電視台拍攝,再加上音樂是大家耳熟能詳的皮亞佐拉《自由探戈》,該錄影截至執筆之際已有超過十八萬六千次瀏覽量,為整個Phil Your Life with Music系列之冠。

香港中小型藝團大多透過這種合作方式發佈免費網上音樂會,如康文署、大館表演藝術部和亞洲文化協會(香港中心),當中包括香港弦樂團賽馬會音樂能量計劃《美樂共賞》社區音樂會系列和襄聲平台2《襄序曲之春》線上音樂會,為樂團提供網上直播支援或場地不等。

以上各種合作模式不少也是在第一波疫情時開始商討,並在第二波疫情開放場地時錄影或製作。這除了顯示各樂團有能力進行不同數碼製作外,也開始拓展把其演出放在不同平同發佈,甚至銷售的可能性。而香港中樂團更推出「香港網上中樂節」,透過公開徵集作品,播放一系列本地專業和業餘樂團的錄像,算是在疫情中開創網上音樂節先河。但有一點要留意,雖然香港觀眾開始接受欣賞網上演出的模式,但未成為主流。更重要的是,香港不同樂團在此刻沒有像柏林愛樂或美國大都會歌劇院那樣發佈昔日錄影限時重溫。相信除了存檔的錄影未能作出放映外,另一個可能性是要處理網上放映的版權。

場地在此階段關閉七十六日,代表第三波疫情有超過一半時間是不能進行演出。這段時間各樂團主要回歸場地現場演出,能夠同時兼顧數碼錄像製作和發佈的樂團也只有香港中樂團。這個階段大部分網上音樂演出和節目均由康文署製作。

但這些數碼錄像製作更不止以音樂會為主,更趨向電視節目化,如香港中樂團的中樂MV《追月》和康文署的《爵士「不」取消》系列。前者尤如流行音樂錄像,後者在爵士樂演出中加添演奏者講解,讓整個音樂節目更具吸引力。

中小型樂團也大多回歸舞台,而仍有發展其數碼資產的藝團,如美聲匯和竹韻小集等,與康文署合作不同網上節目。而中小型藝團美聲匯也開始透過中介,讓他們的作品在內地及其他地方播放。康文署新視野藝術節雖然取消,但加添網上演藝平台「更新視野」,實行線上線下節目並行。以音樂作品來說,當中最兼備數碼和現場演出元素為《空氣頌》。聲音劇場(丹麥)透過氣流與煙霧的縹緲投影與香港兒童合唱團在香港公園「同台」演出,完全打破地域和疫情界限。除了現場演出外,更有網上版本,讓更多未能參與的觀眾可以在網上感受科技和自然環境的無縫結合。

第四波疫情只有約兩成時間關閉表演場地,但有幾件對香港發展數碼節目的大事發生,包括虎豹樂圃開展「遊弦活樂」線上音樂節全直播節目、康文署文化節目組Facebook 和YouTube 更名為「藝在「指」尺」、香港藝術節並行網上及現場演出,和香港藝術發展局的Arts Go Digital 節目於二〇二〇年十二月三十日開始發佈獲資助的節目。筆者特別提及虎豹樂圃開展「遊弦活樂」線上音樂節全直播節目,因為是首個在古蹟活化場地舉辦的網上直播音樂節。這個場地若非早前有和流行音樂合作直播音樂會的經驗,要處理一個先天設計不是為古典音樂會設計的場地進行古典音樂會的演出,其實也有一定難度。另外,二〇二一年第49屆香港藝術節的開幕演出,香港中樂團的「樂旅中國」作網上與現場同步演出,雖已不是新鮮事,但也算是香港首個大型藝術節作此安排。

下文主要以Arts Go Digital 作為分析香港中小型樂團和音樂藝術工作者在後疫情時代的得著,特別是Arts Go Digital 獲資助的樂團和音樂藝術工作者大部分在疫情之後已有機會進行網上演出,包括香港作曲家聯會、一才鑼鼓、竹韻小集和美聲匯。

Arts Go Digital 大部分音樂節目的意念有趣,而且幫助了不少本地藝術家發表新音樂作品,但呈現方式卻有很大差異,當中涉及資助額、藝術家數碼知識和製作數碼節目經驗。由於每個申請團體或藝術工作者只有三十萬至五十萬元進行數碼創作,若與不同藝術家進行合作,如一才鑼鼓在新網站發表了過百首微音樂新作。從作品量推算,它們可以用運用在數碼呈現的資源有限,因大部分資金會用作支付版權費。而一才鑼鼓再自行推出了十二集網上YouTube 節目作推廣,不計較瀏覽數字,已算是把資助金額物盡其用,又如何計較在數碼呈現上是否合乎美學呢?另外,藝術家的數碼知識也大大影響音樂作品的美學呈現。以鄺展維和梁基爵的網頁作比較,分別在音樂意念和故事性很強,但其網頁呈現卻大大影響了觀眾對音樂作品探索的意欲。前者的網頁實在似中學生初學網頁的作品,若要連結上《22世紀殺人網絡》經典黑底螢光錄字的大量數據跳動動畫,也甚為牽強; 後者在進入網頁後,會自動播放音樂和動畫,明顯可以讓人探索不同房間內容。事實上,網絡世界有如此多節目選擇,網絡觀眾不會像現場觀眾般有耐性探索一個視覺或資訊上毫不吸引的網頁。當網頁不吸引時,觀眾便沒有興趣點擊任何連結。若網頁沒有自動播放音樂,基本上觀眾在沒有聽到任何音樂作品下,便因視覺不吸引,很快轉向瀏覽其他更吸引的網頁或節目。然而,梁基爵也在訪問中分享『申請到50萬資助,他笑仍是「有少少賴嘢,做大咗個頭,大家都蝕晒本」』[9]。若具備數碼知識的音樂家也感到五十萬其實不足以製作互動元素和美學兼備的音樂網頁時,其他缺乏數碼知識的音樂家在製作相同質素網頁時更為百上加斤。所以香港藝術發展局在資助數碼作品時,也應考量藝術家的數碼知識是否足以讓作品在網絡上有合適的美學呈現。當然,音樂創作者本應只需集中音樂創作,但疫情也突顯他們的數碼知識如何大大影響作品在網絡的呈現。

鄺展維《下一個現場》

鄺展維《下一個現場》

梁基爵《超連結大廈》

梁基爵《超連結大廈》

而疫情中的數碼錄像經驗,也大大影響樂團在Arts Go Digital 的作品。本人認為眾多Arts Go Digital 的音樂影片之中,美聲匯的《冰上〈冬之旅〉》音樂和視覺俱備,把 《冬之旅》這個故事在溜冰場上拍攝,加上柯大衛的落力演出及成博民和劉中達的導演手法,整個網上觀看體驗不單止出色,也感受到《冬之旅》那種寒徹骨的無奈。同時也看到美聲匯在與康文署及其他團體的合作之中,吸收了不少錄像製作經驗,並把傳統音樂作品透過專業的錄像製作提升至另一個新高度。

疫情突顯香港樂團和音樂藝術工作者不得不走向數碼化。但整個過程之中,除了突顯業界缺乏場地和器材支援外,更重要是大部分香港樂團和音樂藝術工作者在疫情前未具備足夠製作專業質素的網上或電影節目能力,以確保其創作在不同平台呈現專業質素。當政府在支援各樂團和音樂藝術工作者創作以保生計,是否更應同時考慮如何幫助業界提升他們的數碼知識水平,以應付全球競爭激烈的網絡世界呢?

然而,這些專業質素的數碼節目是需要大量資金的長久支持,並非一時三刻可見到成果,而樂團和音樂藝術工作者更應考慮的是:自己的作品是否適合結合藝術科技或走向數碼化?如果是朝這個方向發展,是否把自己的音樂作品直接放上平台,還是要針對平台的觀眾在形式上有所改動,以確保觀眾有一個完善的音樂藝術體驗?如果並非朝向這個方向發展,其實不應為受資助而「科技」。這無疑確保生計,但卻是浪費社會資源。

[1] 薩依德:〈極致瞬間〉,載《音樂的極境》(Music at the Limits),第141 – 142頁,雷淑容編,莊加遜譯。廣西:廣西師範大學出版社,2019。

[2] 香港特別行政區政府統計處:〈2019/2020住戶開支〉。

https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/tc/scode290.html

[3]大學線:〈藝術疫轉|新冠肺炎疫情下暫別理想 藝術工作者能屈能伸〉,《香港01》,2020年12月20日。

https://www.hk01.com/sns/article/562567?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral

[4] 立法會:《會議過程正式紀錄》,2022年3月23日。

https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr2022/chinese/counmtg/floor/cm20220323a-confirm-ec.pdf

[5] Melissa Lesnie:〈YouTube Symphony attracts 33 million views worldwide 〉,《Limelight》,2011年3月25日。https://web.archive.org/web/20110411054027/http://www.limelightmagazine.com.au/Article/252414,youtube-symphony-attracts-33-million-views-worldwide.aspx

[6] 九個主要藝團為香港管弦樂團、香港中樂團、香港小交響樂團、香港舞蹈團、香港芭蕾舞團、城市當代舞蹈團、香港話劇團、中英劇團及進念.二十面體。

[7] 馬瑞璿:〈線上演唱會憑什麼賣四千 解密背後酷技術〉,《今周刊》,2021年7月14日。https://www.businesstoday.com.tw/article/category/183015/post/202107140027/

[8] 立法會:《西九文化區推廣表演藝術及場地營運的進度匯報》,2021年3月1日。

https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr20-21/chinese/panels/wkcdp/papers/wkcdp20210301cb1-635-1-ec.pdf

[9] 明報:〈科網世代:揼網頁拍片 藝術「超連結」〉,《明報》網站,2021年4月11日。https://ol.mingpao.com/ldy/cultureleisure/culture/20210411/1618080594766/%E7%A7%91%E7%B6%B2%E4%B8%96%E4%BB%A3-%E6%8F%BC%E7%B6%B2%E9%A0%81%E6%8B%8D%E7%89%87-%E8%97%9D%E8%A1%93%E3%80%8C%E8%B6%85%E9%80%A3%E7%B5%90%E3%80%8D

Let us recount the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak: at first, people thought that it was a localised epidemic, and did not expect it to spread for a long time. Epidemic prevention and quarantine measures started to be implemented in various places, but they were not stringent on the whole. Or perhaps it would be more apt to say that even if the authorities did not state it, people were generally thinking, “The pandemic will be over soon, so we should try to minimise the impact of prevention measures on normal life.” Thus, “normal life” became antonymous with “global pandemic”: as COVID-19 began to break out all over the world at an unimaginable rate, we also seemed to have gained a renewed understanding of the term that we know as “globalisation”.

The pandemic was like a radiocontrast agent that identified networks of contemporary global human interaction. We suddenly discovered that even though we often say that cyberspace has eliminated the physical distance between people in the Internet Age, the reality is that it has never replaced face-to-face communication. Be it from the macro perspectives of economics and culture, or at the micro interpersonal and social levels, the same holds true. The so-called “normal life” refers precisely to this kind of “physical contact” between people.

Deaths, quarantines, and lockdowns continued to take place worldwide, and one cannot help but be reminded of literary imaginings the likes of those observed in Albert Camus’s The Plague, or omens pointing to civilisational collapse such as the Black Death during the Middle Ages. However, what is in the imagination stays in the imagination. It turned out that the coronavirus did not lead to excessive speculation about “Armageddon”. The death toll gradually became a number, and the majority of governments around the globe soon made the “resumption of normal life” their goal.

The problem is that the term “normal life” has been completely redefined over the two or so years of the pandemic. People lost the opportunity to communicate face-to-face while undergoing quarantine, but their desire to interact did not only not vanish, but transformed into two types of mindsets. The first hoped to use “staying in touch” as the new definition of “normal life”, even if it was only by online means. Consequently, videoconferencing software suddenly became a necessity of life, while “working from home” also became the new normal; the second was the complete opposite and loathed “online communication”. Reiterating the negative and “technophobic” remarks about social networks mentioned in the past, those of this mentality drew on such commentary to justify the need to “resume (pre-pandemic) normal life”.

Because of the emergence of effective vaccines, some governments were able to propose “coexistence with the virus” as a condition for resuming normal life, and subsequently accelerated the pace of restoring operations across all sectors in society. On the other hand, some governments insisted on a “zero-COVID” policy, thus resulting in a delayed recovery. However, regardless of policy, there is no way of avoiding one fact: having lived in isolation and completely replaced face-to-face communication with online interaction, people can no longer pretend that they don’t need – or at least don’t need to rely on – online communication. To put it in another way, the quarantine life amid the pandemic has forced us to contemplate which aspects of “normal life” still require “physical experience”. And how does the “normal life” that we now lead online differ from the way we used to live?

It was under this backdrop that contemporary theatre was thrust into uncharted territory. Into the third year of the pandemic, Hong Kong theatre still has not “fully” returned to the pre-COVID “normal”. This problem is attributed to at least three factors:

The first has to do with the operating and production “norms” of theatre troupes. Due to fluctuations in the COVID-19 situation and the government’s anti-epidemic policies, performance venues were closed at short notice from time to time, or required to operate at reduced capacity and accommodate fewer performances. On January 29, 2020, the Leisure and Cultural Services Department announced the closure of all performance venues for the first time. With the pandemic remaining persistent in the past two or so years, venues have closed and reopened repeatedly. At the same time, audience numbers, as well as the epidemic prevention requirements for performers and viewers, have also been changed every now and then. Such circumstances made it impossible for troupes to carry out production planning in a “normal” way. On the one hand, they had to bear the risk of increased costs resulting from not being able to perform or the reduced number of shows and audience members. On the other, they had to formulate backup plans to reduce the corresponding pressure, such as switching to the streaming of live or recorded performances.

The second is related to the viewing “norms” of audiences. Spectators are no longer strangers to “online theatre viewing" after living in isolation. The virtual world became indispensable during the pandemic, and even things that we used to think were only possible onsite could be done online. “Working from home” is a clear example. Others such as online classes, online lectures, virtual museum tours, and even online Chinese New Year gatherings, have also become commonplace. Putting it in another way, when we plan an activity nowadays, “onsite” and “online” are both options. Because of COVID-19, people are more inclined towards the latter choice. Theatre audiences are also fully understanding of a troupe’s decision to present online performances, and have gradually grown used to this kind of viewing experience.

The third pertains to the “norms” of the theatre itself. Although it seems that we have become accustomed to the virtual life, and increasingly see “onsite” and “online” as two equal options that do not connote “normal” or “backup”, with the popularisation of “online theatre”, we (including creators, audiences, and critics) must also reconsider a question regarding the nature of theatre itself: If it does not take place onsite, is theatre still theatre? Or we could ask the following: What kind of theatre can theatre be if it does not take place onsite? The global pandemic has not only fundamentally changed the mode of theatre creation, but also inspired our imaginings of contemporary theatre. While the number of Hong Kong theatre productions has drastically diminished over the course of the pandemic, the discourse on contemporary theatre aesthetics has unexpectedly flourished.

What is certain is that the (forced) online shift has greatly stimulated the minds of theatre creators, spectators, and critics alike. Creators must take practicality into account and consider how transferring a performance to cyberspace will affect its aesthetics and production conditions, as well as how it will change the way they create; audiences need to learn to adapt to this structural shift in order to enjoy a viewing experience that is similar yet different to that of the past. Such audience experiences may either be more autonomous or more constrained; as for critics, in addition to commenting on the merits and shortcomings of individual works, they must go one step further and pay attention to how this kind of revolution in the realm of theatre influences the presentation of works, audience reception, as well as the future development direction of the discipline, and even how it may lead to the rewriting of contemporary theatre modes on the theoretical level. These are all issues that Hong Kong theatre must examine in the (post-) pandemic era.

Creators mainly dealt with theatre’s online transition in the two following ways:

The first was to regard online performance as an expedient measure to maintain regular presentations. With many works originally intended for in-venue performance being “forced” to go online, creators often did not give too much thought to “online performance” as a mode, and could only use the easiest method of playing back the recording of the actual performance or dress rehearsal in the theatre. The camerawork in these recorded performances is relatively simple, with hardly any consideration given to the differences between live and screen viewing. Thus, the resulting footage is often dull.

The second was to stream previous performances online to maintain a troupe’s exposure. With the reopening of venues remaining in a state of indefinite postponement, some of the bigger and more established troupes made their back catalogue available for online viewing for a limited time. These videos were originally only recorded for documenting and archiving purposes, and not intended for public broadcasting at all, so the quality is generally poor.

There are quite a few examples of the two above cases during the early days of the outbreak. However, creators, troupe operators, and viewers alike were generally dissatisfied with these “works” – the main reason was not creative quality, but rather, the “online” presentation format. Let us cast aside purely technical issues such as streaming platforms first – many theatre companies were not familiar with what “online theatre” was at all, while spectators were also unaccustomed to the corresponding viewing experience. Theatre audiences require “training”. That is to say, they gradually become acquainted with the “liveness” of the theatre through frequent attendance. This “liveness” includes the rational processing and judgment of the content and messages of a work. More importantly, it also involves the integrated perception of various senses, i.e., a kind of “experiential” or “immersive” affair. Online viewing completely nullifies this experience that theatregoers have accumulated over many years. A lot of audiences had bad experiences with online viewing because they felt removed. The specific contributing factors are as follows:

The first was the lack of liveness. The Internet and the camera became barriers between the audience and performers. Viewers were clearly aware from the very beginning that they were not in the same physical space (the theatre) as where the performance was taking place, thus the theatre experience which they have come to know so well could not be reproduced.

The second was the loss of the sense of ritual. One enters the auditorium, the lights dim, and then the performance begins – this was a mandatory “ceremony” for theatregoers in the past. However, online viewing has eradicated this ritual. Firstly, spectators could not “go to the theatre”, nor could they interact with other audience members and creators before and after the performance. This already marks the first step in “the loss of the sense of ritual”. Viewers also did not have to watch a show at a fixed time and place – they simply did so “in the comfort of their own home”. While viewing a production online, they would either do other things at the same time, or be distracted by activities that usually take place at home, such as eating casually, chatting with family members, and going to the toilet. This further diminished the sense of ritual associated with going to the theatre. In terms of sensory perception, the experience was not much different from watching TV or surfing the Internet.

The third is sensory restriction. One of the advantages of live theatre is that the audience has the freedom to choose what to watch/receive. Many viewers found that the online format limited their perspective. Since there is often more than one thing happening on the stage/performance area, the presence of actors in different places, together with staging techniques, gives rise to a whole yet multifaceted picture. However, the camera is in control when watching recorded footage/livestreams online. It might give you a panoramic view at a particular moment in time, or it might give you a close-up of an actor, or even a certain body part of an actor. This could be the director and cameraman’s personal choice based on aesthetic or technical considerations, but it completely limits the viewing angle for the “at-home” audience on the other side of the broadband connection.

As for the differences between the in-venue and online formats, many people have noticed the two following points:

The first is related to the boundary between theatre and film. Traditionally, “mise-en-scène” is thought to be the biggest difference between the two. This term originated in theatre, but later became widely used in film. It refers to how a creator (mostly the director) arranges various elements in a work. As a matter of fact, the two disciplines share many similarities, from content (story, plot, dialogue, actors, etc.) to method (the use of scenes, lighting, sound, etc.). Nevertheless, “mise-en-scène” fundamentally distinguishes one from the other: the mise-en-scène in theatre takes place on the stage/in the auditorium, while that in film occurs within the screen. This also extends to the temporal difference observed in the two formats, i.e., stage productions consist of a continuous string of events taking place onsite, while there is a sense of temporal disconnection in cinematic works due to the editing involved.

Online theatre is a means to cinematise stage productions. National Theatre Live, with which Hong Kong audiences are relatively familiar, does exactly this: it films theatre performances using cinematic mise-en-scène techniques for presentation on the silver screen. Yet, the online versions of Hong Kong theatre productions amid the pandemic generally failed to achieve this visual quality, with costs being one key issue and production experience another. More importantly, however, this approach requires creators to have this awareness of “theatre filmization”, so as to be able to offer spectators a “cinematic” experience rather than a “theatrical” one. Nevertheless, many of these Hong Kong stage productions which were broadcast online lacked this creative awareness, and instead further magnified the differences between the two disciplines, thus interfering with the audience’s viewing experience.

The second has to do with the nature of theatre itself. It seems appropriate to quote Peter Brook’s famous words once again here: “I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.” This statement has become a reference point where reflection on online theatre is concerned. Undoubtedly, the concept of “defining theatre as ‘empty space’” has always been a constant in Hong Kong theatre. The key elements of “empty space” are as follows: space, viewing, being viewed, and a live setting. The Internet, meanwhile, is a platform which removes the contexts of “space” and “live settings”, making the “empty space” notion difficult to practise.

Similarly, the online format also destroys the “viewing” relationship between audiences and performers. The “empty space” concept requires the viewer and the viewed to be in the same setting for an act of theatre to be engaged. According to this definition, online theatre is not “theatre” at all. And as long as creators and spectators continue to embrace this theory, so-called “online theatre” can only be an expedient and temporary presentation strategy – people will eventually demand to “return to the theatre” so that the “norm” of the “empty space” can be restored.

Nevertheless, protracted pandemic and quarantine measures have not only caused people to lose patience, but also changed their perception of theatre on a fundamental basis. It can be said that theatre in the post-COVID era is undergoing a contemporary paradigm shift: “empty space” is no longer so essential, and the differences between theatre and film have blurred. More importantly, the cyber migration of social interactions resulting from living in isolation became the catalyst for revolutionising our imaginings of theatre. Creators began to ponder one question: If we must continue to create online theatre (not as an expedient or temporary strategy), how should we handle the tensions between the “online experience” and the “theatre experience”?

As a result, theatre has not only been freed from the confines of the stage once more (the first time was possibly when Bertolt Brecht broke the fourth wall of realist theatre), but also brought into people’s contemporary online experience for the first time: we once believed that there were certain physical interactions, such as the theatre experience, that could not take place online, but as the pandemic of the century continued to spread, even theatregoing began to be included in the list of activities that could be done virtually. Once people accept this idea, a whole new problematic in Hong Kong theatre presents itself. And even if the epidemic eases and performance venues reopen, this problematic will not go away: How do we incorporate the online experience into theatre creation?

In fact, this problematic is nothing new: immersive theatre, which has become popular around the world in recent years and also deeply influenced Hong Kong theatre, is the exact same deal. Immersive theatre breaks the traditional theatre framework, putting emphasis on how stage works construct the overall audience experience beyond simply “watching”. Consequently, immersive theatre makes extensive use of Brecht’s “epic theatre” techniques, as well as methods from movements such as environmental theatre and Happening, to directly introduce the audience into real-life social experiences. When Hong Kong theatre creators are attempting to handle the interactions between the Internet and the theatre, they must first figure out how to turn their personal online experiences into a form of theatre – for instance, the use of social media platforms, streaming technology, and video conferencing software, or even the interactive functions of online games, video channels, and message boards.

Let me cite a few examples. Reframe Theatre’s How to present the love life of Hong Kong people to Aliens in the time of pandemic was adapted from an old work by director Yan Pat-to, with the original “lecture theatre” format, which took place in the physical theatre, changed to one resembling an online class. Additionally, the creator enabled the messaging function of the online communication software, allowing the audience to send instant messages. The creator’s intentions are very clear: to simulate the online class experience in real life, i.e., to try to organically integrate the online experience into the work, so as to rewrite the relationship between performers and audiences. Theatre critic Jeffery Lin pointed out that, on the one hand, the viewers’ instant messages bring “a sense of realism” to the narrative of the play, but on the other, they “distract” other audience members, thus highlighting the various shortcomings of the script. The narrative of the work and the “narrative” instantly woven by the audience might complement each other, but they might also compete with each other, vying for the viewers’ attention and “taking the play in another direction”.[1]

Lin also compared two other works which were presented via video conferencing software. In the mini auto-ethnotheatre production, See You Zoom, the four actors shared how they lived under the pandemic using the titular software, and then opened the virtual floor to discussion. However, Lin believes that the creators overcontrolled the way in which viewers could respond to the content. For example, audience members were asked to give scores and only allowed to answer specific questions, which prevented them from expressing their opinions in depth.[2] As for Riceball Association’s Table for Two, creator Jennifer Lam held 100 online performances over the course of four months, each time inviting one viewer for a chat in her virtual restaurant. Lin thinks that the work was only designed to have a frame and a set of procedures, while the content was formed through the real-time conversation between the actor and audience member. To him, this kind of chance encounter in virtual space may be “the beginnings of a new type of theatre”.[3]

Lin’s comparison underscores how the online migration of theatre can rewrite the relationship between performers and audiences. Firstly, although the sense of liveness has vanished, the real-time interaction has, on the contrary, proven to be more vigorous and effective than live theatre. However, whether this kind of interaction can produce a form of theatre close to that of Augusto Boal’s style, in which the audience is heavily involved in the narrative of a work, depends very much on how the creator uses the tool that is “cyberspace”. As per Lin’s analysis, See You Zoom had an excessive grip on interaction, How to present the love life of Hong Kong people to Aliens in the time of pandemic was too loosely structured, while Table for Two had to rely on the ability of participating viewers – in the role of amateur actors – to handle the content and mode of interaction (this also requires a form of “acting skill”), in order to generate effective exchanges.

In addition, Lin also critiqued a work modelled after online games: R. U. Human? by Inspire Workshop. The production simulates an online game using virtual office software, and allows viewers to freely explore the spaces and events in the system. Lin believes that the biggest difference between this type of online theatre and interactive film is that the former requires all audience members to be simultaneously present in the time-limited gaming space. This “co-presence” not only affects the rhythm of the work, but its collective nature also directly determines the direction of the narrative, differentiating this format from interactive film, wherein choices are made by the individual. However, Lin also pointed out that figuring out how to create live theatre’s sense of collective ritual and intimacy in cyberspace is also an issue that requires further exploration.[4]

Since the advent of the Internet, online experiences have been integrated into contemporary life at speeds both swift and slow. Swift because Internet technology has developed rapidly and its rate of popularisation has increased exponentially; slow because contemporary society has always been wary of Internet technology – on the one hand, we remain vigilant about the decline of face-to-face communication caused by the Internet, and on the other, we worry about being subjected to surveillance in our daily lives and fear the arrival of the “Digital Leviathan”. Nonetheless, a global pandemic has greatly accelerated the internetisation and virtualisation of contemporary life. People were forced to give up most in-person meetings and cast aside their cyberspace fears, so as to stay in touch with others and not end up in a state of ontological loneliness. Meanwhile, Internet technology has also reshaped the way we exist as individuals as well as our sense of togetherness as a collective.

All these have become factors that theatre creators cannot avoid and must intervene with cautiously when producing online works. Meanwhile, critics have to continually question the effectiveness of these efforts and update our understanding of contemporary theatre. Yan Pat-to, who is both a theatre director and critic, is optimistic that the online format is a step “towards decentred performance modes” in theatre. He even drew on Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction theory, pointing out that the cyber migration of theatre, or even theatre-generated mediums (he cited several online theatre works that incorporated elements of audio dramas and online videos as examples), have departed from the centre that is the “traditional definition of theatre”.[5] What Yan did not clarify was what the “traditional definition of theatre” was – he was most likely referring to Brook’s classic definition of “(in-person) theatre”, which indeed seems to be a form of “theatre-centrism”. Because of apandemic, we may have found a path to “decentralisation” through the Internet.

However, this optimism cannot mask people’s apprehension about the future of theatre. While we believe in the possibilities of the discipline’s future, we also have grave fears for its demise. The three following aspects precisely represent how people imagine the future of theatre will be under the pandemic:

The first is liveness. The call for “returning to the theatre” has never ceased, with most creators still insisting on the live experience of the “empty space”. However, many people also believe that as long as we broaden our understanding of “liveness”, we will find that online experiences can also offer a kind of “(virtual) liveness”. It must be noted that “virtual” is not synonymous with “fictitious”. It is just another (or the “most contemporary”) experience which, especially in an era of pandemics, has permeated everyone’s daily life, changing people’s perception of “life” at a fundamental level. A more conciliatory way of putting it would be that “physical” and “virtual” are not mutually exclusive. The online platform will not destroy theatre, but only serve to expand its definition.

The second is publicness. Discourse on the “publicness of theatre” has always existed and, in addition to works of “political theatre”, is also a plea for new modes of theatre, i.e., how to manifest the publicness of social or political issues through theatre formats or aesthetics. The most direct observation is that, due to its liveness, theatre can become a space in which performers and audiences interact, hence making it conducive to the formation of public opinion. Works that belong to Augusto Boal’s school of theatre are the most representative where this is concerned. In Hong Kong, meanwhile, the practices of Playback Theatre are also quite on-trend.

Nevertheless, the Internet’s function as a contemporary performance space that embodies publicness is old news. In particular, from the social movement in Hong Kong which spanned several years, people have already recognised the Internet’s power to shape public opinion and even mobilise social movements. Consequently, a number of people (like Yan) are convinced that, just like various other political and cultural domains, the Internet can be used as a means of “decentralisation” in theatre: in cyberspace, audiences can have a deeper involvement in a performance than in the conventional theatre, and even engage in immersive participation more easily, through the use of social media platforms, message boards, or messaging software. But on the other hand, we can also hold the completely opposite opinion and see this kind of “decentralisation” via the Internet as a form of “atomisation”: it isolates audience members from one another, and also separates them from the performers. The spectators’ “participation” in the public exchange of the theatre is actually just virtual and imaginary in nature, rendering it even more detrimental to real public dialogue. This is evident in Lin’s analysis.

The third is cultural democracy: it is undeniable that “decentralisation” is a key concept of the online format. Especially with the rise of blockchain technology in recent years, people cannot help but think about the possibilities of “de-institutionalisation” in theatre creation: for example, troupes may no longer have to rely on government funding or be subjected to market logic. The use of the Internet or other technologies not only helps reduce costs, but also eliminates the absolute constraints of scheduling and venue space, facilitating more flexibility in both “troupe creation” and “audience viewing”, as well as reflecting a form of cultural democracy to a greater degree. Felix Chan, who is both a drama critic and theatre producer, has proven that online theatre offers various possibilities for theatre companies and creators with his own production experience amid the pandemic. The format can free them from complete reliance on government and market resources, enable them to create more flexibly and freely, as well as further facilitate fairer collaborations between creators with different backgrounds and abilities, and from different regions, thereby bringing about universalisation in cultural production.[6]

However, this subjective desire may only be an ideal that has yet to take shape. The theatre system has never been easy to revolutionise. The pandemic has only created a “suspended moment” for society, forcing people to think about the possibilities of change. But when COVID-19 subsides or becomes an “everyday norm”, this collective experience of suspension will gradually wane, and the conservative voices of those who wish to return to the “old normal” and rebuild the “system” will re-emerge. This struggle is mandatory, and exactly the same as that associated with any form of social change.

(Translated by Johnny Ko)

[1] Jeffery Lin. “The Metaphors of Online Production: Anxieties About the Value of Theatre and the Future”. Artism Online, October Issue, 2021.

https://artismonline.hk/issues/2021-10/489

[2] Jeffery Lin. “Online Theatre Under the Pandemic: The Cultural Politics of Media and the Emergence of New Genres”. IATC (Hong Kong) website, uploaded on July 15, 2020 (in Chinese).

https://www.iatc.com.hk/doc/106376

[3] Jeffery Lin. “Online Theatre Under the Pandemic: The Cultural Politics of Media and the Emergence of New Genres”. IATC (Hong Kong) website, uploaded on July 15, 2020 (in Chinese).

https://www.iatc.com.hk/doc/106376

[4] Jeffery Lin. “Theatre in the Cloud: The Boundaries Between Gaming, Interactive Film, and Theatre”. IATC (Hong Kong) website, uploaded on July 21, 2021 (in Chinese).

https://www.iatc.com.hk/doc/106583

[5] Yan Pat-to. “An Accidental Practice of Decentring – An Overview of Online Performances in 2020”. In Chan, K.W., Chu, K.O., and Wong, K.M. (eds). Hong Kong Drama Overview 2019 & 2020. IATC (Hong Kong), 2022.

[6] Felix Chan. “A Contemplation on Whether Hong Kong Can Develop Cultural Democracy Through Online Performance”. IATC (Hong Kong) website, uploaded on February 23, 2021 (in Chinese).

At the beginning of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic broke out and ravaged the world. Although the various anti-epidemic policies adopted by governments around the globe have helped reduce the number of deaths caused by the virus, almost all industries had to shut down, severely impacting people’s lives. Hong Kong, an international city where trade and cultural exchanges frequently take place, was obviously no exception. As endless restrictions became the norm, many sectors gradually began to develop various coping strategies to weather the storm as best they could while the pandemic persisted. To prevent anti-epidemic measures from excessively affecting economic activity, the Hong Kong government provided exemptions for people who must work in congregate settings amid social distancing restrictions.

Unfortunately, such exemptions did not apply to theatre workers. Although performances were allowed to resume to a limited extent when the epidemic eased, for Hong Kong theatre practitioners, the fluctuating situation did not bring about a so-called “new normal” to which they could adapt, but a perpetual limbo between the complete suspension and partial resumption of performances – the end of one coronavirus wave only meant that a production had to be completed as quickly as possible and presented at the theatre before the next wave struck, leading to much chaos. Learning about the emotional roller coaster that theatre practitioners have been experiencing since the outbreak of the pandemic is probably the only way for us to truly understand the severe impact that multiple performance suspensions has had on the performing arts sector, as well as the yearning of industry members to escape the fate of having their productions cancelled and their efforts going to waste as they warily went about creating in the face of uncertainty.

It is also only in this context that we can come to comprehend that online theatre, which emerged in 2020, is far from a fad. On the contrary, it serves as a means to document survival during difficult times. Through this platform, we are not only able to catch a glimpse of theatre practitioners’ struggles between ideals and disillusionment, but also fully appreciate the incredible adaptability they demonstrate in the creative process and the tenacious spirit with which they practise their craft.

In two in-depth interviews, representatives from four Hong Kong performing arts production units shared their experiences in creating online theatre during the pandemic. The resources and aesthetic strategies of each organisation are different, thus giving rise to diverse forms of “online theatre”. The sharing of these invaluable experiences should help us better understand how the Hong Kong theatre industry ought to face the difficulties posed by reality and search for possible ways forward while navigating uncharted territory.

Forced Emergence and Independence: The Production and Creation of Online Theatre Under the Pandemic/Adversity

Despite also bearing the “online theatre” label, the handful of experimental and vague works prior to the pandemic are incomparable to the performances that became prevalent after the COVID-19 outbreak and gradually gave shape to the genre through intensive practice. As mentioned earlier, the main driver behind this particular online theatre boom was more of a forced reaction to reality rather than the result of proactive exploration. Nonetheless, the misfortunes and helplessness that exist in reality are manifold in nature, and to find the right direction, it is necessary to understand how the “alternative plan” of online theatre can become a creative outlet for different theatre companies given the circumstances. The sharing by the theatre practitioners in the interviews will likely enable us to gain a deeper understanding of the point of departure of their respective teams in making online theatre, thereby leading to a better grasp of the aesthetic concepts they have each developed.

When it comes to commissioned works, the final decision does not lie with theatre practitioners. Consequently, this type of production unit can be considered the most passive among all. For example, Chan Tai-yin, the director of The Plague (Cantonese version) which was commissioned by the Hong Kong Arts Festival, said that he always prefers performances in a physical setting. Upon learning that the organiser decided to switch to the online format due to the fourth COVID-19 wave during the rehearsal phase, he still fought hard for a live performance in the theatre. Unfortunately, he did not succeed and had to film the production for online viewing as requested by the commissioning party.

Hong Kong Arts Festival - The Plague (Cantonese version)

A more common situation was that after learning its work could not be staged in the theatre during the production process, the team would have no choice but to choose to go online, simply because the alternative of outright cancellation meant that their creative efforts would be in vain. Desmond Tang, the director of We Draman Group’sThe Days of the Commune, recalled finding out in mid-2020 that the work could not be performed live due to anti-epidemic restrictions. However, the troupe was three-quarters of the way through rehearsals at the time, and therefore did not want to waste the creativity they had already put in or miss the opportunity to discuss Bertolt Brecht’s theatre aesthetics. Ultimately, a decision was made to film the performance and present it to the audience as a broadcast. Meanwhile, Janice Poon, the director of PORNOGRAPHY, produced by The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (HKAPA), said that the performance of this work constituted the coursework of the graduating class at the HKAPA. It was originally scheduled to be staged at the academy’s theatre, but students were required to stay home after the pandemic broke out. After consulting the students’ opinions, she learned that everyone still wanted to continue their studies, and so decided to switch to the live online performance format. The presentation came to a successful close at the end of May 2020.

In contrast, the creative background and experience of the Hong Kong Repertory Theatre’s 2020 re-run of Principleare slightly different. The show was originally scheduled to take place from the end of September to October that year but, unfortunately, the third coronavirus wave hit Hong Kong in July. Although the epidemic had slowed down by late August and various restrictions had been relaxed gradually, it was not until October that the authorities reopened theatres to allow the resumption of live performances at half capacity. After being forced to cancel its late-September shows, the troupe was finally able to perform live in early October. At the same time, it decided to launch a livestream version to offer audiences another way to appreciate the work. Sunnie Lai, Senior Manager (Production) of the Hong Kong Repertory Theatre, explained that the company hoped that more viewers could have access to this production, hence the decision to include the livestream option, facilitating the simultaneous presentation of the performance in both the offline and online setting. Nonetheless, the play’s director Fong Chun-kit admitted that his first priority was to take care of the audience in the theatre, which shows that the majority of theatre practitioners still favour the physical environment.

Regardless of the reason for the decision to create online theatre, the persistent epidemic had left all theatre practitioners at a loss. It seemed that everyone was mostly going about their work with a “take things as they come” attitude, thus they were generally inclined to regard online theatre as a stopgap measure. It was also because of this that there was a desire to create productions in a way that would restore the liveness of stage performance. Indeed, the long-term brewing of thoughts and practice took place behind the experimentation, as it is something that cannot be accomplished overnight. Instead of unrealistically expecting the epidemic to instantly provide myriad creative opportunities for online theatre, it would be better to actively learn from the experience of an inevitably rushed first attempt in anticipation of the next production.

However, we all know that familiarity with one’s tools is a basic requirement of creating art, and when it comes to restoration, technical experimentation and practices are bound to be involved. It is precisely because of this that each team spent time exploring numerous shooting techniques during the creative process. During the interviews, the theatre practitioners shared with us their respective approaches to exploring various techniques in unfamiliar territory.

For example, Tang stated that when filming certain scenes with fewer actors in The Days of the Commune, he did not limit himself to the conventional three-camera setup, but wanted to put more thought into camera positioning. The Film Director of Principle, siUbo hO, also pointed out that he especially designed two unique camera angles for the livestream version of the work: one camera was placed directly above the stage, and the other in the audience seating area facing the middle of the stage, so as to highlight some details in the play that even the live audience might not have noticed. Similarly, Apple Ng, the Video Director of The Plague, explained that she intentionally chose an aspect ratio wider than the 16:9 standard for most films when shooting its performance, so that a better sense of the theatrical activity taking place at the venue could be captured.

For production teams with relatively tight resources but low creative pressure, such time-consuming explorative processes are often difficult, but may also bring surprises. PORNOGRAPHY serves as a reference-worthy example in this regard. Poon mentioned that although the HKAPA approved the switch to the online format and also provided sufficient support in terms of publicity and other related matters, the entire production was put together by those involved in the play. The performance took place at the home of one of the student actors, thereby practically making it a “zero-cost” production. She added that the students put a lot of effort into figuring out how to carry out scene changes with the online platform, and even incorporated technological elements such as visual effects. Fortunately, they were able to master the characteristics of the platform after multiple trials and succeeded in delivering the desired viewer experience.

It is encouraging to see these technology-related gains resulting from the production of online theatre. Nevertheless, as stated above, the use of the virtual environment to temporarily replace the physical one is an extreme measure in extreme times. Consequently, it was unavoidable that theatre practitioners had to adopt a “DIY” spirit in order to flexibly respond to the various constraints that came with the real working environment. If one of the challenges in the production of PORNOGRAPHY was that the actors had to rely on resources in their immediate environment, then the difficulty in the filming of We Draman Group’s The Days of the Commune lay solely in the capturing of moving images in the theatre. Tang expressed that because it was decided that the performance would be shot in the troupe’s rehearsal studio with live sound recording, the air-conditioning had to be turned off. However, it was the middle of summer at the time, so one can imagine the ordeal that the actors had to endure during the filming. Moreover, the studio is situated in an industrial area, so shooting could only commence when the surroundings quietened down after working hours. As a result, performances and filming often continued into the night. The location of the theatre also posed an obstacle to the recording of The Plague. As Chan recalled, they were not made aware that filming had been arranged to take place at Cattle Depot Theatre until the late stages of rehearsal. Subsequently, they had to figure out a way to integrate the in-situ steel pillars into the set design within a short timeframe. Ng added that due to the insufficient depth of the stage, it was necessary to avoid the use of long shots.

We Draman Group - The Days of the Commune by Bertolt Brecht (Source: We Draman Group Facebook Page)

Relatively speaking, although Principle was performed live in a traditional brick-and-mortar theatre with its online version seeming to be merely an added option, the team faced other challenges on the livestreaming front. As hO explained, while filming equipment is fairly affordable nowadays, due to the presence of an audience, he could not move the gear during the performance. Therefore, he had to “plant” multiple cameras in different locations throughout the venue beforehand. Lai also said that to ensure the smooth viewing of the livestream, it was necessary to contact the network provider in advance to obtain sufficient bandwidth. In addition, she revealed that many copyright issues must be dealt with when it comes to online theatre, going on to elucidate that one of the main reasons behind the Hong Kong Repertory Theatre’s decision to livestream Principle instead of the translated version of the play Le Père, which was forced to close due to the COVID-19 outbreak at the time, was that there was a film adaptation of the latter, rendering it almost impossible to obtain the rights to livestream the play. Similarly, she explained that it was also necessary to obtain the online broadcasting rights to the music featured in the play. Thus, if they were to convert a play that was soundtracked by a lot of popular music into an online performance, the potentially hefty costs involved would rack up a substantial production bill.

Intertwined Fates: A Dialogue and Mutual Interrogation on “Liveness” Between Online and Offline Viewing Culture

Although theatre and film both fall under the performing arts umbrella, the two are nothing alike. It is difficult to compare their conventional viewing modes, and the audiences that they attract are also different. For creators, mastering the above-mentioned techniques related to filming equipment or video conferencing is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to a format change. They must conduct an in-depth investigation into the similarities and differences of the two artforms to establish their own positioning.

Similarly, it would be wishful thinking to simply attach the “online” label and assume that audiences will automatically transition from one form of traditional spectatorship to another viewing/screening mode that even the creators themselves are still figuring out. Several interviewees shared with us how they dealt with the challenges in bridging with contemporary viewing culture in the process of making online theatre, including how to rethink the unique viewing mode of theatre to embed an indelible sense of nostalgia and longing for “liveness” in video footage.

To create a work with aesthetic continuity, the members within a team must obviously first come to a fundamental consensus. The theatre director and their film or video counterpart must also agree on the positioning of the performance medium. For troupes whose sole performance medium or “product” is online theatre, this is even more self-evident.